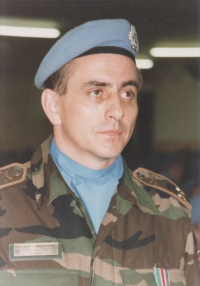

Ing., Lieutenant Colonel (ret.) Rostislav Šmehlík

* 1955

-

Because I say - seeing once, feeling it, is better than hearing it a hundred times and seeing it on video. But to try it yourself, what it is - and this was the good thing that they gave us at the two-year officers' school and then also at the university - that I didn't teach anything in theory that I hadn't experienced myself. I knew very well what it was to have blisters from an engineer's shovel when I dug a trench, when I dug beds for anti-tank mines and crawled two hundred meters... So we were all soaked - and then when I started serving already as a superior, as a commander of a platoon, company, battalion, I knew what is in human possibilities and what it brings. That is, the shouts of someone over there, a politrak saying: "What is it here, you had it differently!" and the like, I say - OK, Comrade Major, whatever you like, engineer shovel, show the boys how it should be done. "Ah, what are you allowing yourself to do?!" - Well, then let it go, I evaluate that they fulfilled the task as I set the task. All done. And what is your opinion, decide somewhere else.

-

When the wife was Slovak and the children went to a Slovak school, and I had to decide after the revolution where I would go or not - no one could know how it would turn out - whether Slovaks would be discriminated against in the Czech Republic or the other way around. And when I considered that the children should be judged somewhere in the classroom because they are Slovaks, I took the risk that I would rather endure some discrimination than my three children and my wife, so I decided to stay in the Slovak army. There I also signed the oath and everything and finished my military career in the Army of the Slovak Republic. And my opinion is that if I have to serve in Slovakia, learn Slovak properly, speak Slovak. I also studied grammar a little so that I could also express myself in writing... - so in my thirties I learned where there is a soft "i" and a hard "y" and so on. I managed it quite well and I have no problem with Slovak.

-

I, as the deputy commander, was in charge of checking the fulfillment of the tasks of those workplaces, which at that time had already been launched practically throughout the territory. Not Serbia, but Croatia and especially Bosnia and Herzegovina. And as I said, there were tasks that were not condemned by the local population, on the contrary, they were accepted and they were happy that they could also use the things we built or made. A very special atmosphere was created there, when the Croats as such, and then the Bosnians, were more or less happy that Slovakia, as they called it, was there, because we helped them in many things. We built a bridge that was used by the UN, but locals could also use it, they didn't have to drive 15 kilometers around when they had a kilometer across our bridge. And similar things. Also the fields, field roads, and so on, where we demined and there was a protocol that was signed by the "Slovak Battalion", so those people also accepted it, they knew it, there were already marked places that were demined and where it was not yet it is certain that there may be mines. Because hundreds of thousands of mines were laid in Yugoslavia.

-

We also had similar other things there regarding demining, because who has never been in a demining suit and does not know what it is like to crawl on the ground in 35-degree heat and poke there with a mine spike or try with a mine detector, then he sometimes says: "Why it's taking so long, why is it going so slowly?" So then I stood in the back and said - Look, you can dictate what you want, but here the one in the suit dictates the pace. He dictates it. Because he stays in it for an hour and a half and has to rest for two hours. In a cooled room, because he would be overheated and take it off healthily. Here the pace is determined by the sappers, those who practically clear the mines. So you can push as much as you want, I'm not going to order them to speed up because there will be a risk of a mine being left there and killing an innocent person.

-

There was a V3S driver who drove - after a certain period the people could also go home, they could go to the deserter - and the driver drove them from Sarajevo to Daruvar and of course he coughed on the car, he had little oil in the engine, he didn't check, the engine stalled and the guys they missed the plane. Well, what now? So they beat him, of course - they ran out of patience, he got a couple of punches. There weren't any teeth knocked out or anything, but there were bruises and he came to complain that hento... I told him - and what do you want from me now? You can relate to the situation of the twelve people you had in the truck, can you relate to that situation? That they are looking forward to going home and only thanks to your sloppiness... No - I will punish you for that, I will take you away from the vehicle and you will not get any deserters, you will be here. He closed his mouth, left. So - I wanted to emphasize again that in such situations, on such missions, every person is important, everyone has their own function, that function is connected to others, and only a well-functioning mechanism can make a sound at the end. An out-of-tune piano will not produce a good sound.

-

Full recordings

-

Galanta, 02.08.2022

(audio)

duration: 04:00:09

Full recordings are available only for logged users.

I will tell you honestly that as a soldier I am probably the biggest pacifist there is, because I have seen the consequences in real situations

Rostislav Šmehlík, born on February 19, 1955 in Moravia, was for more than 30 years a professional soldier of the Czechoslovak and subsequently, despite his Czech nationality, the Slovak army. He graduated from higher military schools in Vyškov and Moscow and served most of his career in the sappering unit in Sereď in advanced command positions. After the division of the republic, with regard to his family, he decided to join the armed forces of Slovakia, and in the years 1993-1996 he was a participant in the peacekeeping missions of UNPROFOR and UNTAES during the breakup of Yugoslavia for 25 months in the positions of deputy commander and commander of the Slovak sappering contingent. After returning to Slovakia, he worked for eight years as the deputy chief and head of the peace missions department at the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Slovak Republic, and after retiring he worked as a sales representative of Česká zbrojovka for post-Soviet European countries and the states of the former Yugoslavia. He is currently retired and lives in Sereď.