I had emigrant dreams at night

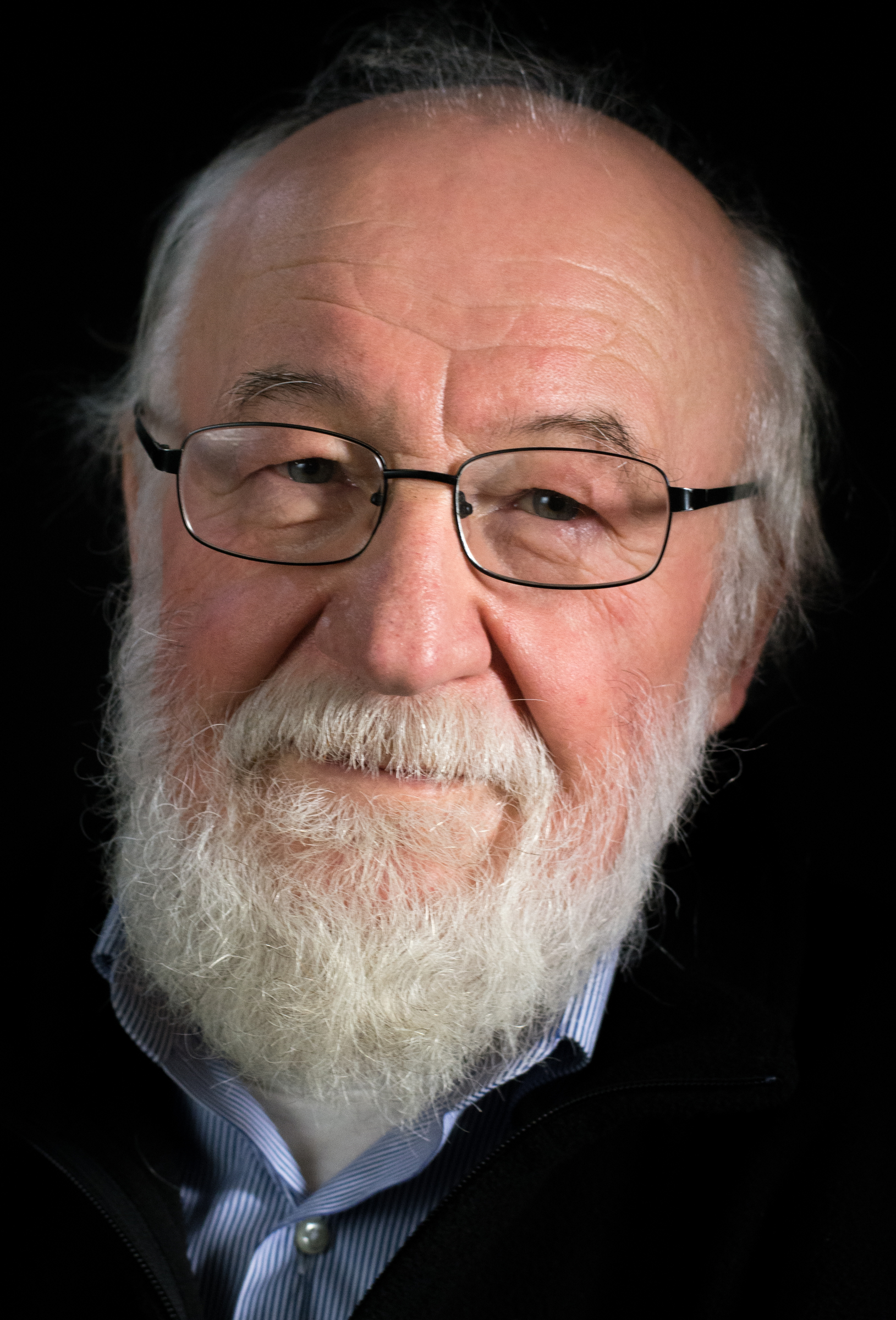

Vladimír Škoda was born on 22 November 1942 in Prague. As a child he had a great affinity for drawing, mathematics, and physics, but his artistic flair was stunted at primary school, where he was forced to re-train as a right-hander. After primary school he started working as an apprentice lathe operator at ČKD Slaný. He turned to painting again, after completing his training he applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague but was not accepted. This was followed by two years of military service, from 1961 to 1963. Shortly after his return he found employment as a stage hand at DISK Theatre, where he could develop his art. Realising that no one in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was interested in his works, he decided to emigrate to Paris. He achieved this goal in the summer of 1968. After a year in Grenoble, Vladimír Škoda enrolled at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris. He met his future wife there, and together they won the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1973, which included a two-year scholarship for both of them in Rome. Upon returning to Paris Vladimír was tenured as a professor and taught at several French universities. Vladimír Škoda’s works have been exhibited in many countries of the world. After the revolution he symbolically returned to his homeland with several exhibitions.