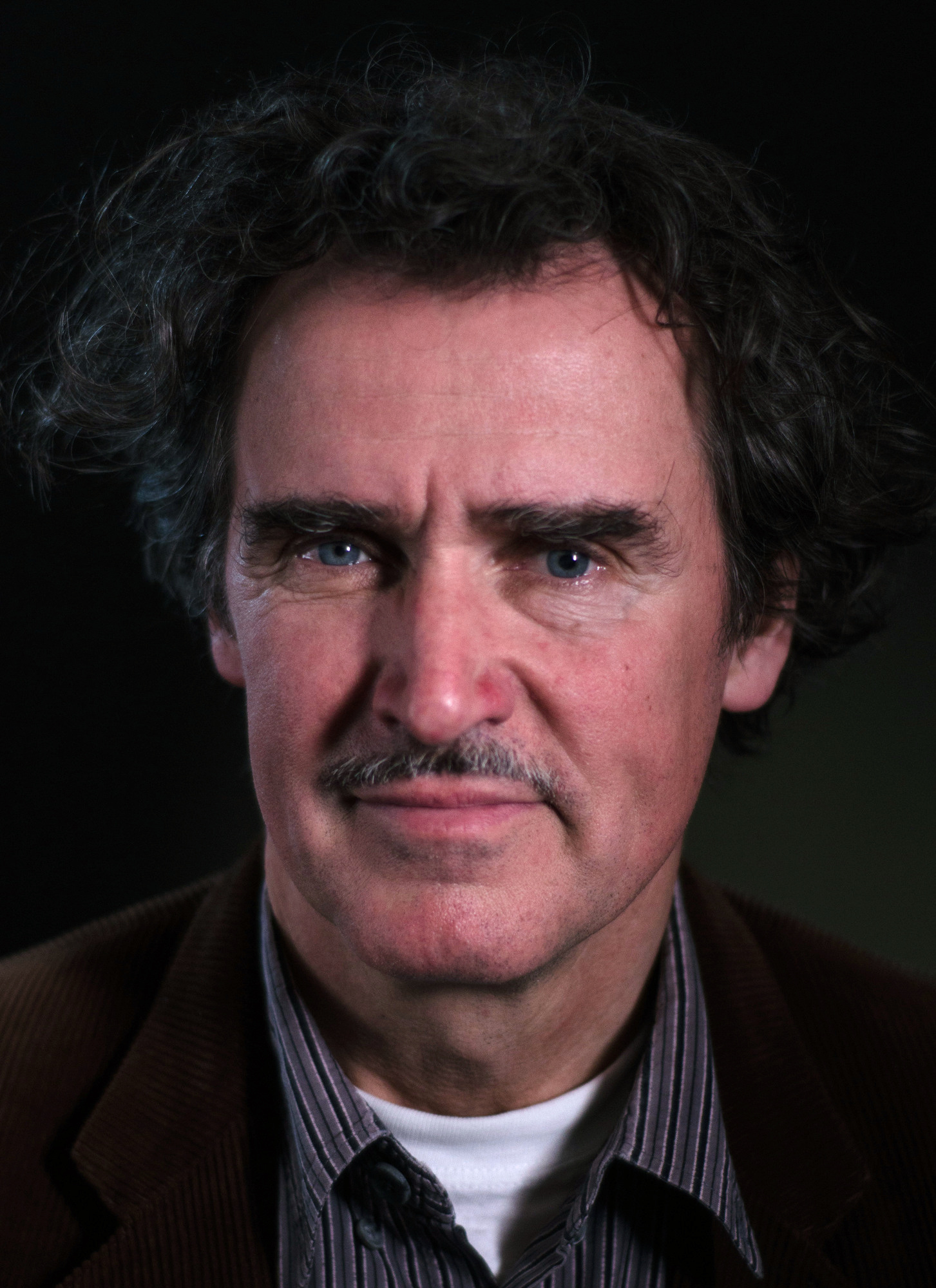

Playing games is a very serious job

Download image

František Skála was born on 7 February 1956 in Prague. His father was a painter and his mother a choreographer. He had spent his early years at the periphery of Prague’s Strašnice quarter where he and his friends played various games. As a child he started drawing, at elementary school he published an illustrated magazine and drew comic strips. He was also the leader of a school gang and as such was always running into trouble. After finishing elementary school he enrolled at a woodcarving high school in the Žižkov quarter where he had also met his future wife. Every summer, he and his friends would go to the Bulgarian seaside where they lived for several weeks as cavemen. This experience influenced František Skála’s later work. In 1974 he and his friends established a secret artists’ grouping BKS which remains active to this day. Following high-school he unsuccessfully applied to the Academy of Fine Arts. Instead, he had worked for a year as a maintenance man. Then he got accepted to study animated film at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. He had rather devoted his time to painting and sculpture, though. From graduation up until mid-1990s he had made a living as an illustrator. Meanwhile, he was gradually returning to his own art works. In the mid-1980s he had his first solo exhibition and in 1987 co-founded the artists’ group Tvrdohlaví (“the Pig-headed”). After the Velvet Revolution he has had several tenths of solo exhibitions both in the Czech Republic and abroad. In 1993 he represented CR at the Venice Biennale. His 2004 exhibition in Prague’s Rudolfinum Gallery became the most successful exhibition of that year. He is a member of the Sklep Theater and a vocal-dance group Tros Sketos. He is married and has a daughter and a son.