Let nothing frighten you. Let nothing upset you. Who has God in their heart, lacks nothing.

Download image

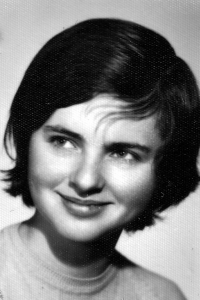

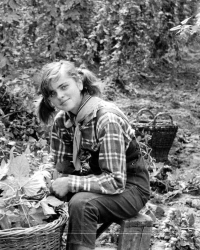

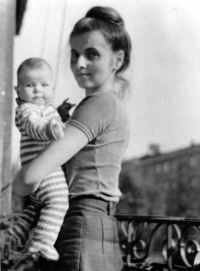

Jana Šilerová, née Žáková, was born on 31 December 1950 in Znojmo. Due to her father’s imprisonment and her mother’s illness, she grew up with her grandmother from the age of eleven. In August 1968, as a grammar school student, she participated in protests in Znojmo against the occupation by Warsaw Pact troops. She graduated from the Hus Protestant Theological Faculty in Prague. After her ordination in 1974, she became a parish priest of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church in Vratimov near Ostrava. With her husband Vladimír Šiler, who was also a Hussite parish priest, she participated in the production and distribution of samizdat literature. She was repeatedly interrogated and followed by the State Secret Police (StB). In the 1980s, she was constantly transferred by the bishop from one place to another as punishment for her activities. She served in parishes in the Beskydy Mountains, and then she was transferred to Rychvald in Karviná in 1984. In 1999 she was elected bishop of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church for the Olomouc diocese. She held the office until 2013. She was the first female bishop in post-communist Europe. From 2001 to 2007 she sat on the Council of Czech Television and then on the advisory body of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. In 2021 she served as parish priest emeritus in Rychvald and in Bohumín.