For communists, religious freedom was a laughing matter

Download image

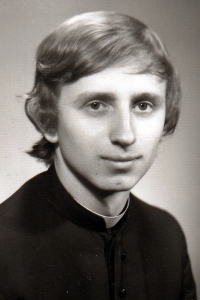

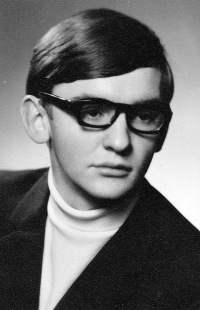

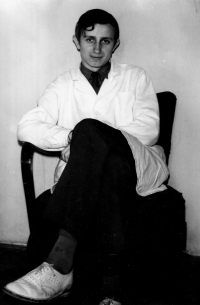

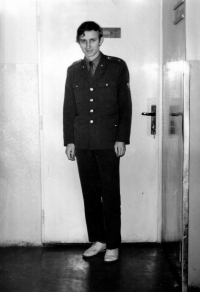

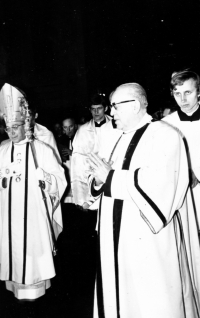

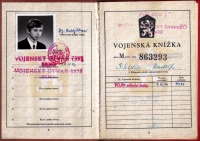

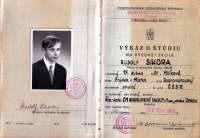

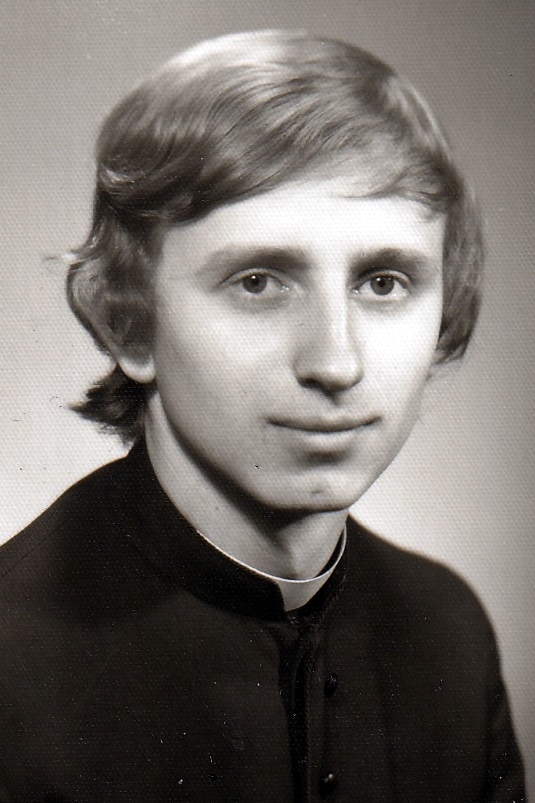

Rudolf Sikora was born on 17 April 1951 in Milíkov near Jablunkov. His parents, Terezie and Jiří Sikora, had five children. They had a small farm and his father was also a blasting furnace operator at Třinecké Ironworks. Rudolf Sikora witnessed his parents being forced to join a collective farm (JZD). They forced his father to sign the document by forcing him to leave his job temporarily. His mother had a nervous breakdown. In 1969, he started to study at a temporarily established faculty of theology in Olomouc. During his studies he took part in printing and distribution of then illegal religious literature. After being ordained he started working as a chaplain in Bohumín. Soon after he had to do his compulsory military service. He had been serving for two years in Brno as a medic. From 1976 to 1982, he was a chaplain in Český Těšín. After that, he was appointed an administrator of a parish in Bílovec. Since his youth, he had been attending secret meetings of the underground church and later he had been organizing unofficial meetings of young people and priests. In November 1989, he took part in forming a Civic Forum cell in Bílovec. In 1990, he was appointed a priest in Hnojník and a dean of Frýdek. In the 2000s, he became an Episcopal Vicar and a Chaplain of His Holiness.