In America, I aspired for Slovakia, now I carry America in my heart

Download image

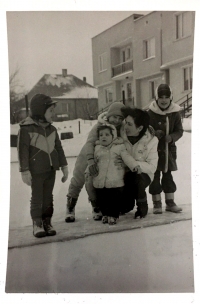

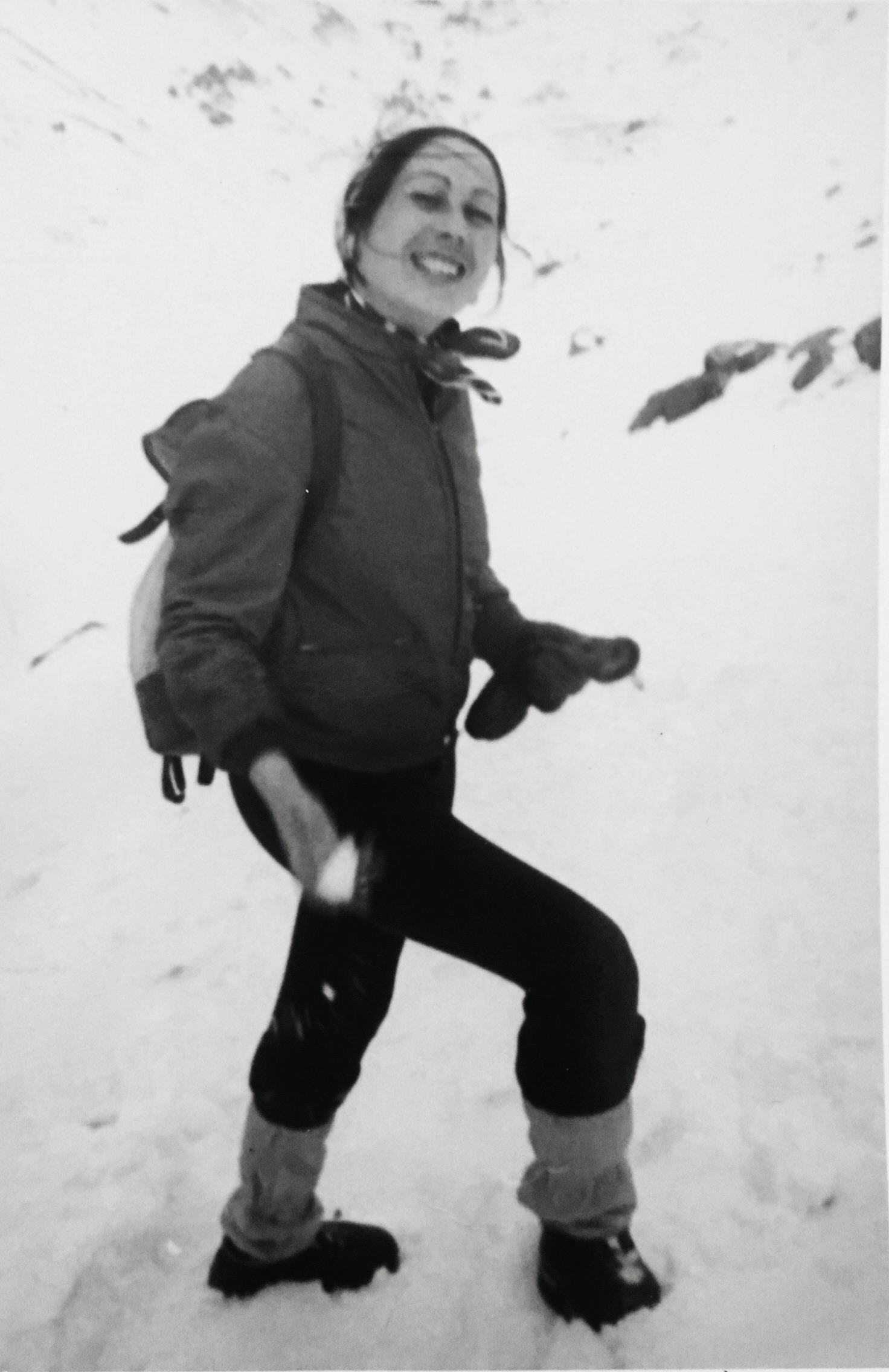

Júlia Ševčíková was born on November 27, 1950 in the village - Hriňová in central Slovakia. She graduated at the secondary medical school and wanted to continue at the Faculty of Pharmacy in Bratislava. However, two of her siblings immigrated to America in 1969 after the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops, and the witness had problems with the ŠtB during her graduation. She could not continue her studies at university. She got a job as a nurse in Liptovský Mikuláš, later moved to the High Tatras. There she met many people whose fate was marked by the communist regime. She also met her future husband there, and they moved to Martin, where they lived before they finished building a family house in Vrútky. In 1980, after the birth of their third child, they started receiving anonymous letters threatening that someone would harm their children. Without prompting, the letter regularly went to investigate the ŠtB. They were sent to them for 4 years. A year and a half after moving to a house in Vrútky, after repeated attempts, they finally got the opportunity to leave the country. In June 1986, the Ševčík family with their four children went on vacation to Yugoslavia, from which they never returned. They emigrated to the USA through the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. In November, they arrived in America and settled in the state of Michigan, in the suburbs of Detroit. In 1992, husband of the the witness was diagnosed with melanoma and it was assumed that he had the last 3 months to live. So she decided to take him to her native Czechoslovakia, where they finally arrived in October 1992. He succumbed to the disease in January 1993. The witess tried unsuccessfully to return the property, which was confiscated by the state after their emigration. Thanks to the husband’s life insurance, the family managed to get back on their feet in Slovakia, but the children had a hard time coping with the new environment, and Júlia with the old environment, where much less had changed than she expected. She still feels the injustice to this day. However, she never returned to America.