I was a Czechoslovak soldier and therefore we did not have to move

Download image

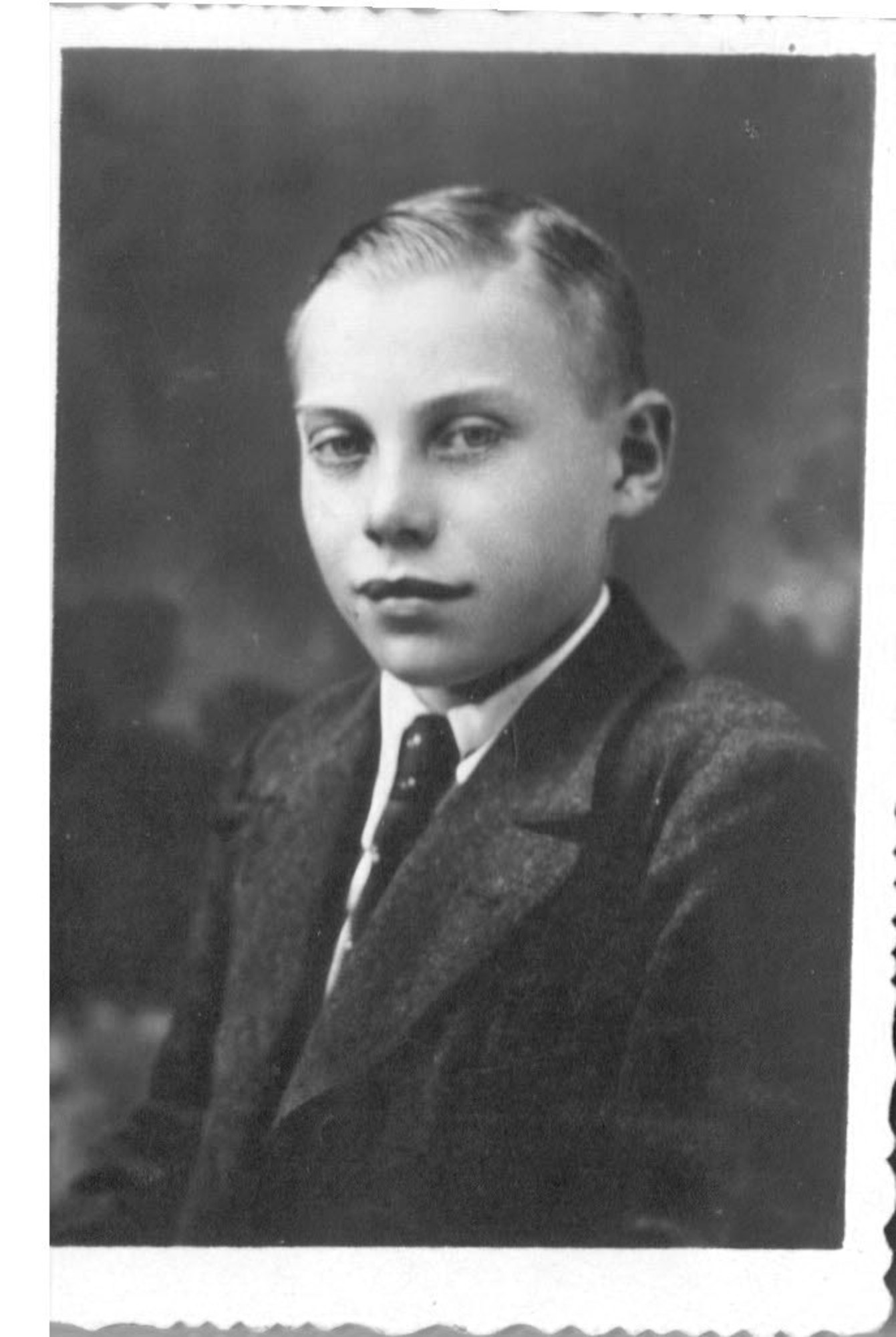

Josef Schneider was born in 1926 in a family of Moravian Croats living in Frélichov (present-day Jevišovka). His father was a railway worker, his mother was a housewife and she was also earning some money by making Croatian folk costumes. There were two children, Josef and younger daughter Marie. During the Czechoslovak Republic, Josef Schneider attended a Czech school like most of the children from Frélichov, and he was brought up in the spirit of patriotism and respect for President Masaryk. After the takeover of the Sudetenland the Czech school was closed down and children began attending German schools. Josef Schneider learnt the locksmith’s trade and in 1943 he had to join the German army. He served in France and the end of the war met him in Germany. After his return home he married Magdalena Schalamunová, who was also a Croat. In 1948 he was drafted to the Czechoslovak army and thanks to being a Czechoslovak soldier at that time, he was not moved out of Frélichov like the majority of other Moravian Croats. His family is thus one of the few original Croatian families who still live in Jevišovka. They had four daughters and Croatian is still spoken in their home.