The miracle of grace is no miracle for love

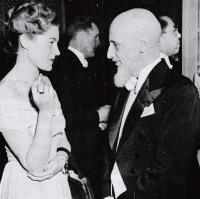

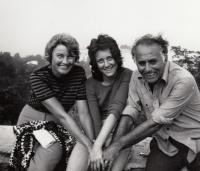

Melanie Rybárová was born on February 19, 1925, in Prague as Miloslava Beranová. She has used the name Melanie since she was given it as a nickname by her then boyfriend at twenty. She comes from a Czech family – her father worked as a lower-rank officer at a ministry, her mother stayed at home. During the WWII she studied at a business academy in Prague. After the war she went to work at the Foreign Ministry, where she met her future husband, Ctibor Rybár, originally Tibor Fischer. He was a Jew from Slovakia who spent the whole war hiding in Budapest. He joined the Communist Party after the war. As an assistant Melanie Rybárová attended many international conferences, including the peace conference in Paris in 1946. In 1948 to 1951 she worked, together with her husband, at the Czechoslovak embassy in Turkey. After their return home, she went to work in the Chamber of Commerce. The Foreign Ministry was hit by the political trial of Rudolf Slánský – the accused included former managers of the Rybárs, Vavro Hajdů and Artur London. A year after the trial her husband was arrested for two months. He was arrested for the second time as late as 1960. In 1968 they thought about emigrating but eventually returned from Vienna to Prague. Melanie Rybárová worked also as a journalist – for Czechoslovak Press Agency or Technical Magazine. Her husband Ctibor Rybár worked in 1960 to 1984 as the editor-in-chief of Olympia publishing house. She retired in 1980 and worked for the next fifteen years as a tourist guide. She and her husband had two children, a son and a daughter, the son has died already.