I’ve come to terms with being dark skinned. That’s just the way it is.

Download image

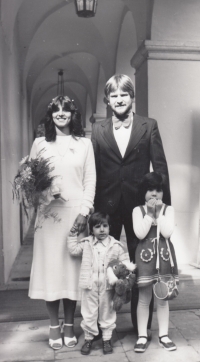

Blanka Rejholdová, née Galbová, was born on 28 August 1956 in Náchod to parents Josefína and Jan, who came to the Czech Republic from Slovakia. On her father’s side Blanka has Roma roots. Her father was a trained butcher, but in Náchod he worked as a stoker in a textile factory, while her mother was already retired on disability. Blanka grew up with three older brothers, in harsher living conditions than her peers. Since childhood she has liked dancing, she went to gymnastics. She attended primary school in Náchod, and in 1974 she trained to be a shop assistant. When she was 16, her father died, and a year later her mother died, too. Her brothers already had their own families and she had to take care of herself. She worked as a shop assistant, and in her free time she worked as a jazz gymnastics and aerobics instructor at the physical education union. In 1992, at the age of 36, she got the opportunity to teach at the art school in Červený Kostelec, which motivated her her to study dance at Duncan Centre Conservatory in Prague. During two years of her studies, she left her job in a shop and got fully involved in working with children at the art school in Červený Kostelec. Soon they became successful in dance competitions and festivals. In 2016 she received the Award of the Ministry of Culture in the field of leisure artistic activities for her artistic and pedagogical aktivity. At the time of recording her story for Memory of Nationa(2022), she was married for the third time, having four children from two previous marriages.