Nobody can see inside your head. You can think what you want. You can know what you want but you have to say that you don’t know anything.

Download image

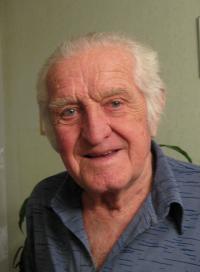

Jiří Rádl was born in Plzeň Doudlevce on January 7, 1928. He grew up with his father and his grandparents. He went to elementary school in Doudlevce and to secondary school in Slovany. In the course of the Second World War, he and his schoolmates from the fourth grade were commissioned to labor in the Skoda works. They were collecting unexploded incendiary bombs. After he graduated from school, he went to the Skoda works to do an apprenticeship as an electrician. In 1944/1945, he was sent to forced labor in Olomouc. He was digging ditches for tanks in the Bruntálsko region. In the chaotic period of April and May 1945, he and a friend of him were crossing all of Bohemia to come back home to Pilsen. They witnessed the arrival of the Red Army to Pardubice. They took the first train from Prague, crossed the demarcation line and they were awaited by houses damaged by bombing. After the war, Jiří Rádl worked in the electro-technical works of the Skoda works in Doudlevce. He was a member of the Union of defense where he met his future wife Vlasta Sikytová. They married on October 30, 1948. By then, he had already joined the anti-communist resistance together with his cousins Milada Kraftová, Libuše Pitorová, František Pitora and Vladimír Jásek. They were collecting strategic intelligence for the U.S. intelligence service. They conducted their activities from July 1948 to June 1950, when the group was arrested. Jiří Rádl was sentenced to 15 years of imprisonment for high treason, espionage and denigration of the court. His wife was sentenced to 9 months of prison. He was put into custody in Carlsbad and waited for his trial in the Pankrác prison in Prague. After the verdict, he was imprisoned in the Bory prison in Pilsen, in the Mariánská camp, Nikolaj camp in the Jáchymov mines, Mírov prison and the Vojna camp in Příbram. In 1956, he was conditionally released. After he was released, he briefly worked in the central workshops in Příbram, the Skoda works in Pilsen and then 20 years as an electrician in the VKD - stone pit construction in Zbůch. He stayed there till his retirement in 1987. Jiří Rádl died in March 2014.