Singing saved me. I had a concert when all my friends got killed by methane

Download image

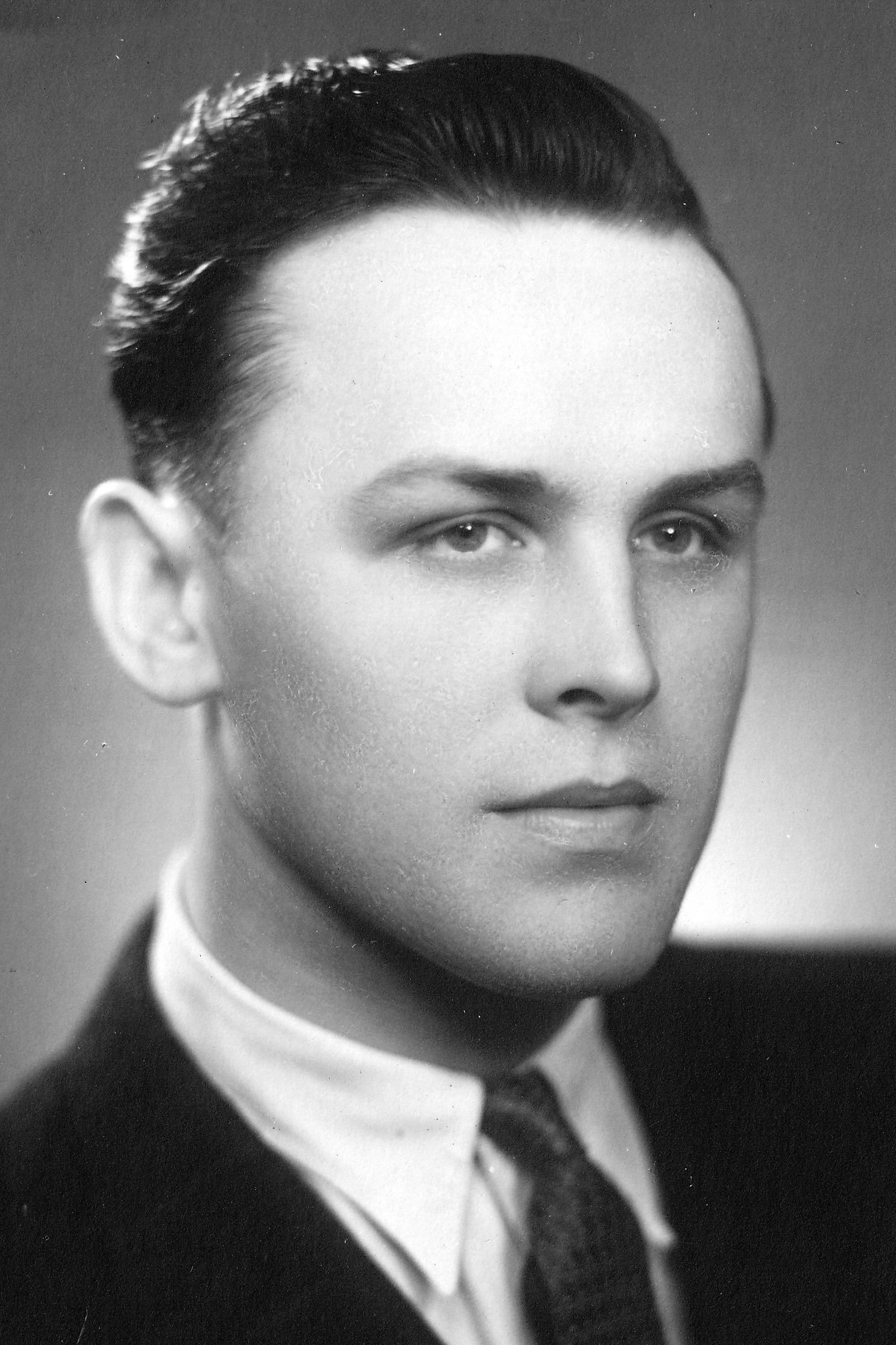

Karel Pyško was born on July 29, 1932 in Orlová. His father had to enlist in the Wehrmacht during the Second World War, when Orlová was annexed to the German Empire as part of the Těšin Silesia. He did not return from the war. Karel Pyško witnessed the Polish occupation of Těšín region in 1938 and the German occupation between 1939 and 1945. At the age of less than fourteen, he began to work in Doubrava mine in Karviná. He graduated from a mining industrial school and then from the University of Mining in Ostrava. He worked in the state-owned company Uhelný průzkum. He got married and lived with his family in Havířov. In the 1960s, he worked at the General Directorate of the Ostravsko-Karvinské doly as an inspector for the prospect of mining in the area. He was a member of the Communist Party, but because of his opposition to the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops in 1968 its leadership expelled him. He had to leave the General Directorate. He then worked in the Karviná mine of ČSM (Czechoslovak Youth) until his retirement, most recently as deputy director. He was responsible for mining preparation. In 2023 he lived in Havířov.