Ruthenians did not officially exist here

Download image

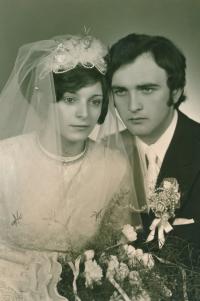

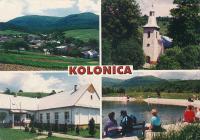

Emília Psárová, née Rošková, was born on September 23, 1955, in Kolonica, East Slovakia, into a Ruthenian family of Marie and Peter Roškovs. She grew up with her four siblings. The family was a member of the Greek Orthodox Church. Emília spent here childhood and youth in her native village of Kolonica, inhabited mostly by the people of the Ruthenian nationality. She went to primary school there, later commuted to Stakčín, where she had, same as her schoolmates, problems with teachers over her Ruthenian faith. Rather than studying, Emília spent more time on the farm, which provided livelihood for the family. Following a serious work injury, her father did not earn any money and her mother’s salary was not enough. Emília trained as a baker in Košice in 1974 and then married Slovak Milan Psár. Shortly after the wedding, they had two children. They settled in the Chomutov region, where her husband’s parents lived and where they got jobs and a flat. Emília worked, until retirement, in school lunchrooms. Around 1990 she met other Ruthenians and joined the Ruthenian group Skeyushan, which remembers and maintains Ruthenian customs.