“You can say whatever you want in the trial, they will sentence you as we wrote anyway.”

Download image

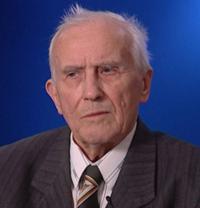

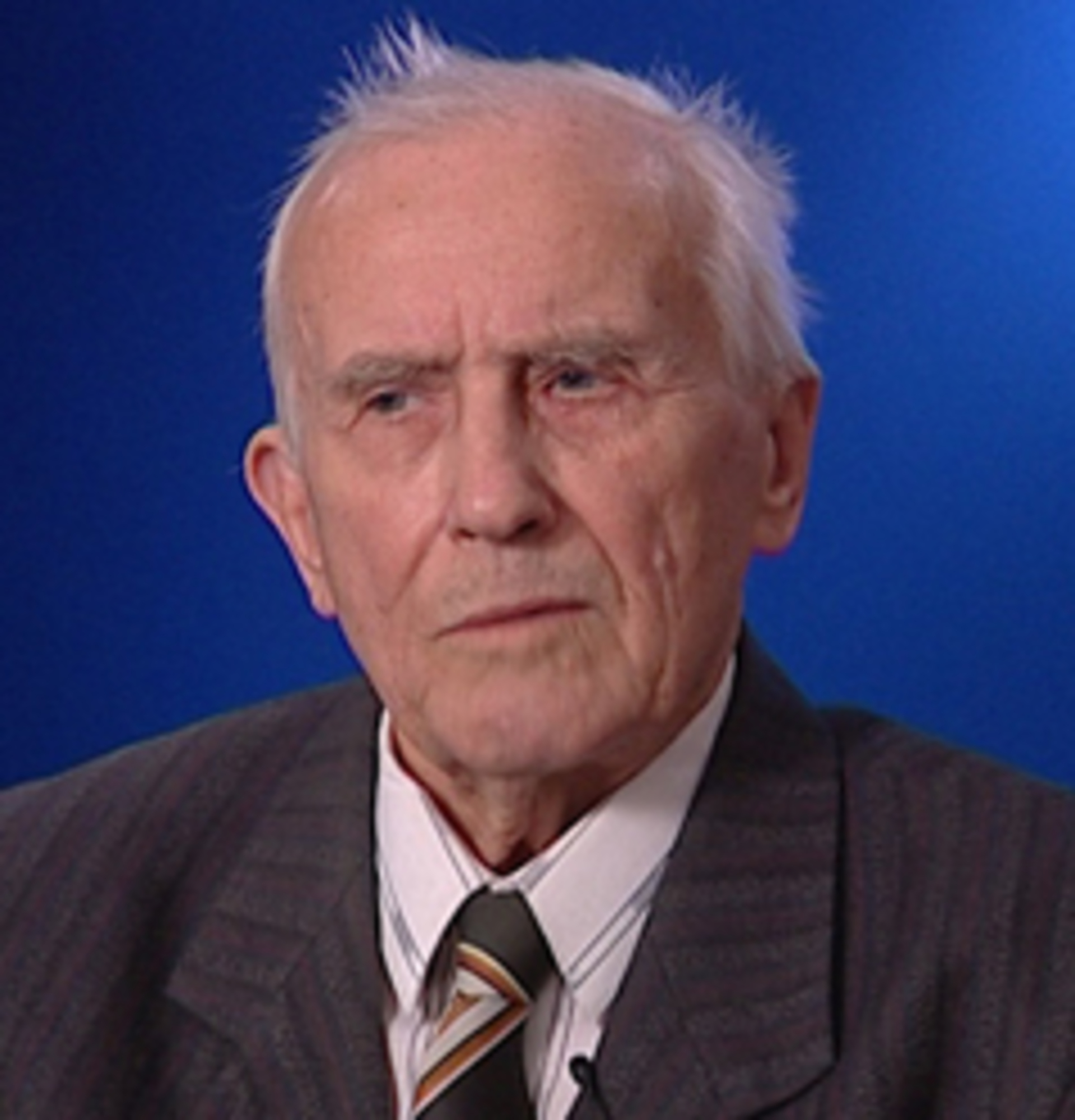

Ján Prokop was born on October 14, 1920, in a peasant family in the village Kriváň near the city Detva. His uncle, Anton Prokop, was executed by hanging in 1919 during the mass by an army of the Hungarian Soviet Republic because of his public speech, in which he had warned people of the invasion and pillage of the Hungarian army. After passing leaving examination at a grammar school in 1941, Ján Prokop continued his studies at the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava, which he finished in 1946. While studying he stayed in the Svoradov dormitory, where he experienced turbulent development of the first Slovak Republic as well as rebellious time during and shortly after the Slovak National Uprising. Due to his participation in the event organized by university students he was arrested and investigated by the State Security, but after being granted amnesty, he was released. After finishing the university, he worked in the civilian aviation. A few years later, he was arrested by the State Security and after a series of investigations and a fabricated trial he was sentenced to two years of imprisonment. He served his sentence in Leopoldov and in Jáchymov prisons, where he had to work hard in mines. Approximately a year later, the Supreme Court in Prague changed the sentence and imposed him fifteen years of imprisonment. Finally, he spent nine tough years in the prison and after being released, he married his long-time fiancée, with whom he had two sons. He was employed as a worker in the construction company Pozemné stavby in Bratislava and later in the company Tesla, where he worked until his retirement. His hobby has been acoustics and he has secretly wired sound systems into forty-one churches in Slovakia.