“We had a political training. When they asked us something we parodied it. And their ‘intelligence’ was so high that they didn’t even realize that we were pulling their leg.”

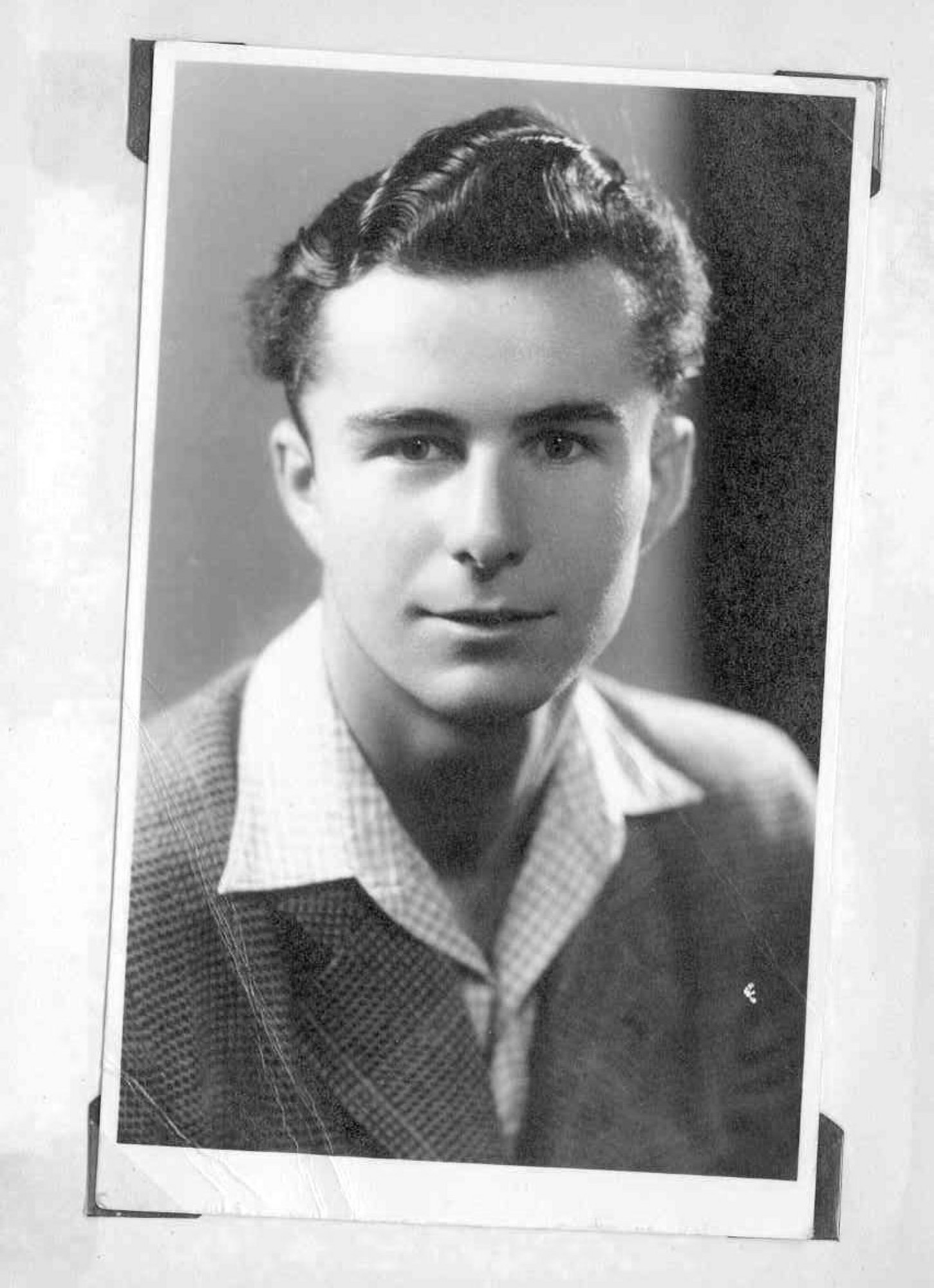

Václav Procházka was born on 23rd November 1932 in Horoměřice where he lived most of his life. His mother worked in the agricultural industry, his father, the chairman of the local branch of the Czechoslovak National Social Party in Horoměřice, worked at the town council. After 1948, he was accused of misappropriation in a staged trial. The accusation was not confirmed but since then Mr. Procházka and his wife were transferred from one job to the other. The police was subsequently interested also in young Václav. He was not allowed to study at the school he wanted because of bad political references. After several unsuccessful attempts, he had to choose a different school - an agricultural technical school in Kadaň. Soon before the graduation exam, he was called to service in the Auxiliary Technical forces (PTP). He joined in October 1952. He served for twenty six months full of hard work and dull political schooling which the regime used to brainwash its enemies and their children. He passed through the basic training in Děčín. From the very beginning the PTP soldiers were treated as human trash and told that they need to be reeducated and cultivated. Václav Procházka was transferred to Pilsen where he worked as a stoker at the construction of military facilities and then he was transferred to the tar layers. In the fall of 1953 he was transferred to Karviná to fill up the used shafts. At the PTP, he worked at several mining positions. The soldiers at the PTP didn’t have any fixed period of the service, it depended on working performance, political testing and the ‘reeducative’ potential. Václav Procházka left the PTP in 1954. He immediately finished his high school education. After the graduation exam, he had to work at positions to which he was assigned by the agricultural production committee. He spent three years working for the worst collective farms in the district. He was constantly politically evaluated. He worked for two years at an airport and then he returned to Horoměřice. He never entered the Communist party and until retirement he worked in worker’s positions as a lorry driver, a grocer, a caretaker, en electrician a helper in a research center. After the revolution he was rehabilitated and refunded in the nationwide rehabilitation of the victims of the regime. He is a member of the PTP association. He does not feel that the service at the PTP would have caused him any health damage, but he admits that it was both physically and psychically demanding and it could at certain conditions affect someone’s health.