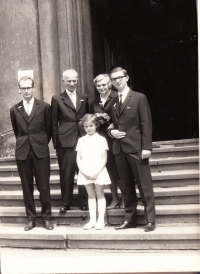

Dad left for work in the morning and came back five and a half years later

Download image

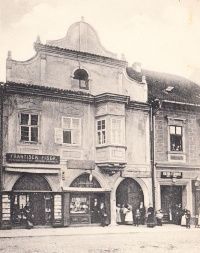

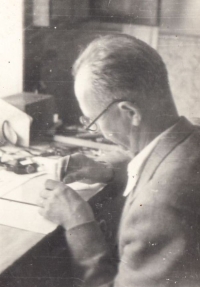

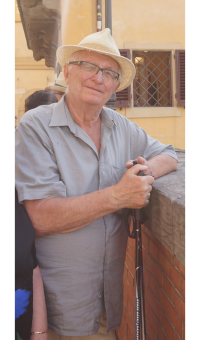

Jan Přibil was born on 1 July 1938 in Třeboň as the second son of watchmaker Stanislav Přibil and Marie Přibilová. At the age of seven he eye-witnessed the end of the war in Třeboň and the arrival of the Red Army. Since the communists came to power in 1948, the Přibil family often came into conflict with the new regime through their anti-communist attitudes. In 1953, his father’s trade was nationalised by transferring it to a watchmaking cooperative. Stanislav Přibil thus became an employee in his own business. Although Jan Přibil was always one of the best pupils at school, he was not allowed to attend grammar school because of his class background and his overall educational path was very complicated. In 1957 he entered a secondary technical school in Prague, where he experienced the most difficult moments of his life. In 1958, a denunciation was made against his father and the communist jurisdiction sentenced him to five and a half years in Mírov Prison for theft of socialist-owned property and violation of the foreign exchange system. Except for a few teachers at school, no one knew that his father had become an enemy of the state. He successfully graduated from school in 1960. He then worked as a technician in various positions in České Budějovice and Třeboň. During political checks in 1970, he refused to sign an agreement with the arrival of Warsaw Pact troops in the Czechoslovakia. He struggled with problems related to his class origin and anti-communist views throughout the entire period of totalitarianism. In 2023, he was living with his wife Mária Přibilová in Třeboň.