“My inscription on the wall of the Civic authorities of Želiezovce, has shone for decades, mentions former political prisoner Pavel Polka.”

Download image

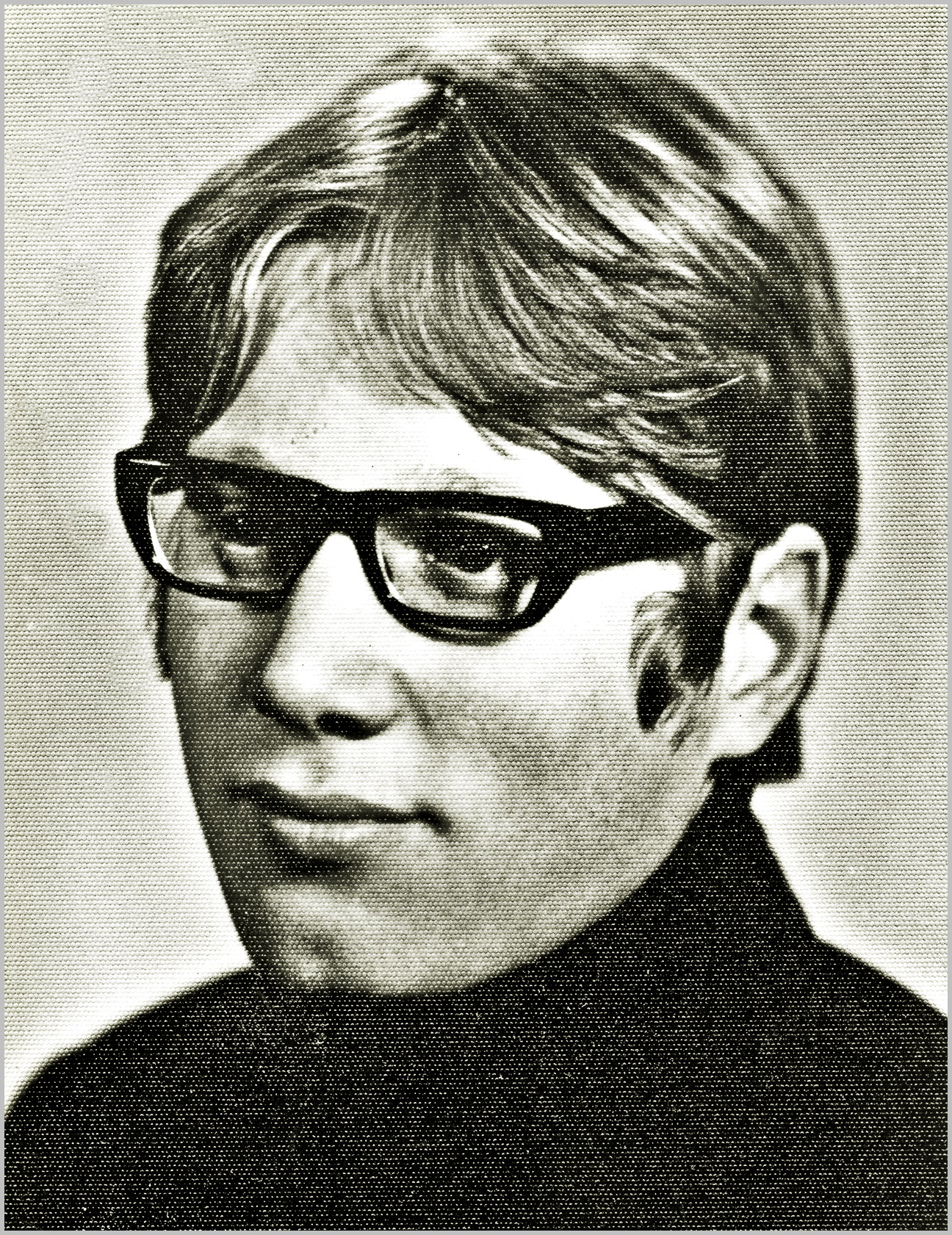

He was born on April 28, 1952 in Želiezovce. Both parents were merchants. Father František worked his way up to the head of the furniture store, and his mother Helena became the head of the bread and pastry shop. His father (born in 1919) experienced the rage of The Second World War, firsthand. As a soldier of the hungarian army, he took part in the fighting in the front line by the russian river Don. It was a certain “curse” for Pavel that his father listened to the broadcast of Free Europe or the Voice of America, and Pavel inherited an interest in public affairs from him. Magdaléna, four years older sister, also had a strong influence on her sibling. She and her mother practically raised her teenage brother. The father died at the age of only forty-five. In 1968, Pavel celebrated sixteen years. When he learned of the occupation, he boarded with a friend on a train bound for Levice. He and his friend started making posters, which they took out. They did the same on the first anniversary of the entry of the Warsaw Pact troops. Pavel wrote the inscriptions “Husák hnusák” and “Vivat Dubček” on his jeans. A woman denoted them to the police. He was brought in for questioning. During the second questioning, he also caught a few blows with a baton. After his confession, he was transferred to solitary confinement and from there straight to court. He should be sentenced to two years imprisonment for the crime of defamation the republic and its representative. In the end, the court sentenced him to three months. Pavel had a lifelong trauma from execution of a punishment. After his release, he began working manually. He managed to get to the evening high school of economics only after years. He did not engage in social affairs during normalization. After the outbreak of the Gentle Revolution, he stood at the head of the local Public Against Violence. He works, as a member of the city council, with a single interruption, from the revolution until now. In the penultimate term, he also sat in the chair of Deputy Mayor of Želiezovce.