He spent the totalitarian times grooving to the rhythm of jazz and swing

Download image

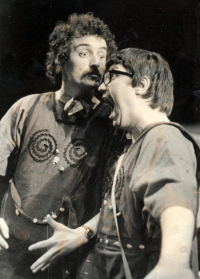

Richard Pogoda was born to Helena and Rudolf Pogoda on August 16, 1944, in Olomouc as the eldest of four children. The father worked as a literary advisor, journalist, and cultural activist. For many years, he was the director of Olomouc’s Music and Poetry Theatre and Film Club. The mother was a primary school teacher. On finishing his eleven-year-long primary school, Pogoda studied graphic design in Prague and then the piano and conducting at professor Preisler’s folk conservatory in Olomouc. Between 1965-1979, he was employed at a printing house in Olomouc as a typographer. In 1965, he joined the Amateur Studio of Oldřich Stibor’s Theatre in Olomouc, for which, along with Pavel Dostál, he wrote several musicals, e.g. “Gaudeaumus Igitur”, “The Cool Guys” (Výtečníci), or “The Prince and the Pauper” (Princ a chuďas). In 1966, he became one of the founders of the Dex Club in Olomouc. After 1968, Pavel Dostál was forced to withdraw from the public eye for his anti-invasion stance, and the creative duo was unable to continue working using their civilian names. Their involvement with amateur theatre continued, staging Voskovec & Werich plays together. Towards the end of the 1970s, Pogoda left the printing works and started working as a DJ and radio editor of shows aimed at young audiences. Shortly before the revolution, he became Miroslav Horníček’s stage partner in his show entitled “The H-Talks” (Hovory H), focusing on Voskovec & Werich’s work. After 1989, he started working at the Czech Radio in Olomouc as an editor and even today, he hosts the so-called Pianotheque. He and his wife Eva Pogodova, a psychologist, have raised two daughters.