The one who survives is the winner.

Download image

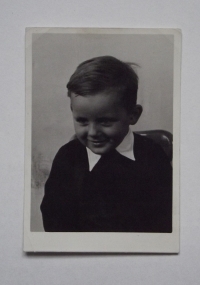

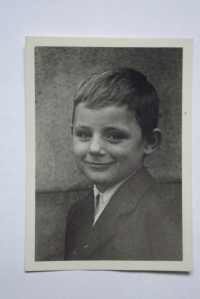

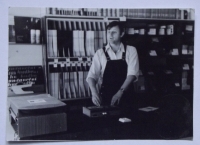

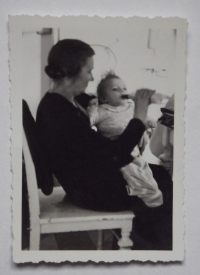

Jiří Pitín was born April 23, 1942 in Lidice, and at the time of the Lidice tragedy he was only six weeks old. At first he was transported to Terezín, and subsequently interned at the infant care institute in Prague-Krč together with some other children from Lidice. His father František was hiding for several days, but he was captured and shot in Kobylisy. His mother took her life in the concentration camp Ravensbrück. His elder sister Marie died in Chelmno with other children from Lidice. After the war, his mother’s elder sister Marie Kvasničková began to take care of him. He graduated in electrical engineering, and then he studied history at the Philosophical Faculty in Prague for several semesters. For many years, he worked as a salesman of audio systems. He is now retired and works for the board of the local chapter of the Union of Freedom Fighters in Prague-Nusle.