I did not want to embarrass the dissent

Download image

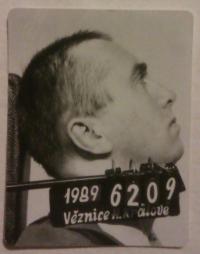

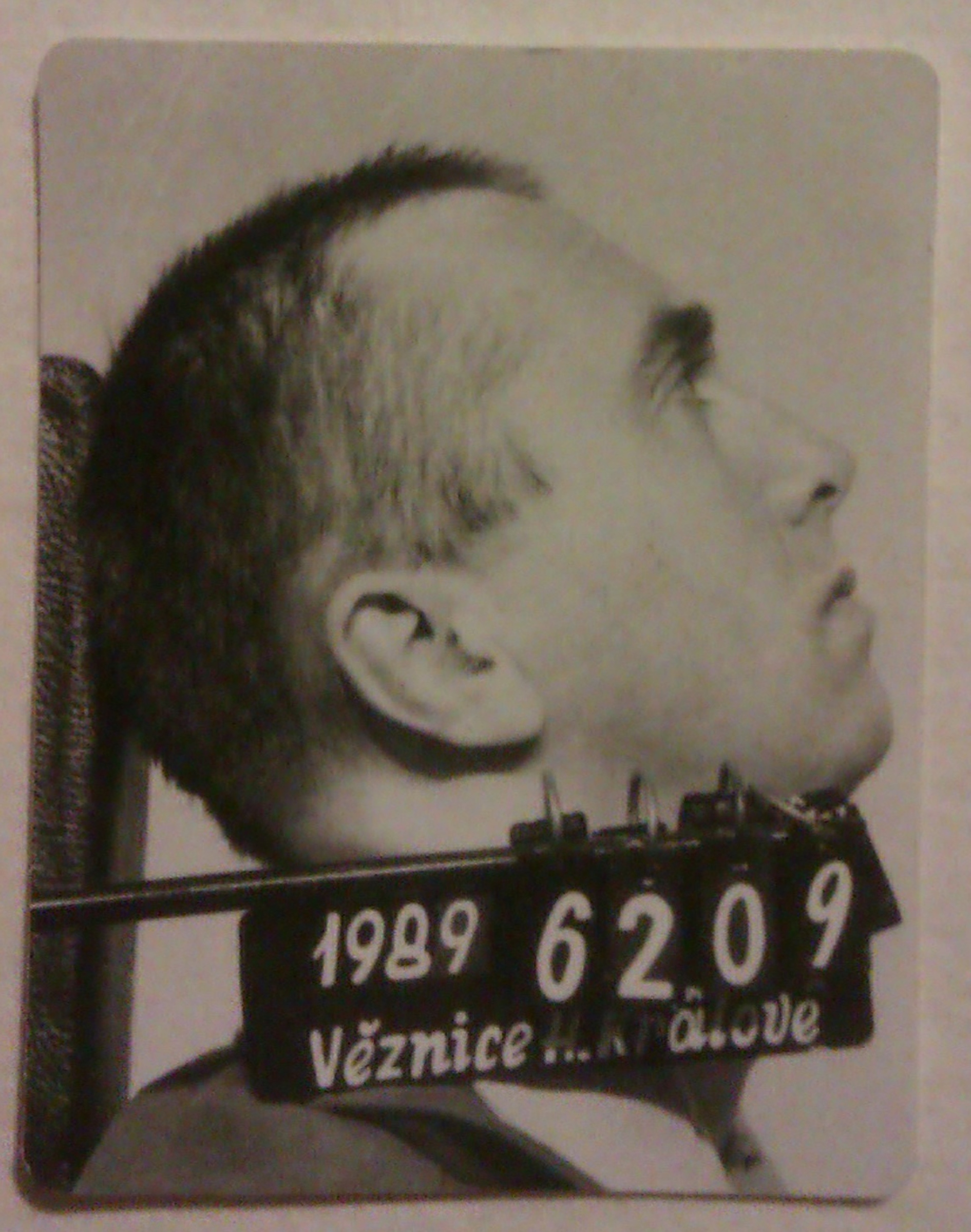

Stanislav Pitaš, also known by the nickname Guma, was born on December 12, 1957, in the village of Kocbeře in eastern Bohemia. He trained in road construction and spent most of his life working as a blue-collar laborer. He became involved with the dissident and underground communities and signed Charter 77. His friendly relations with the Havel family and the community in Nová Ves near Chomutov earned him the permanent interest of State Security. In 1982, he moved to the border village of Šonov in an attempt to escape State Security surveillance, but he was unsuccessful. Between 1985 and 1989, he was imprisoned three times – for undermining the authority of the president, for assaulting a public official, and for stealing socialist property. His mother died during his last imprisonment. After the Velvet Revolution and his release under an amnesty, he became a member of the review commission for the closure of the prison in Žacléř and also a member of the police review commission. For many years, he organized various concerts and cultural activities in his home town of Šonov near Broumov. In 2006, he became deputy mayor of the village.