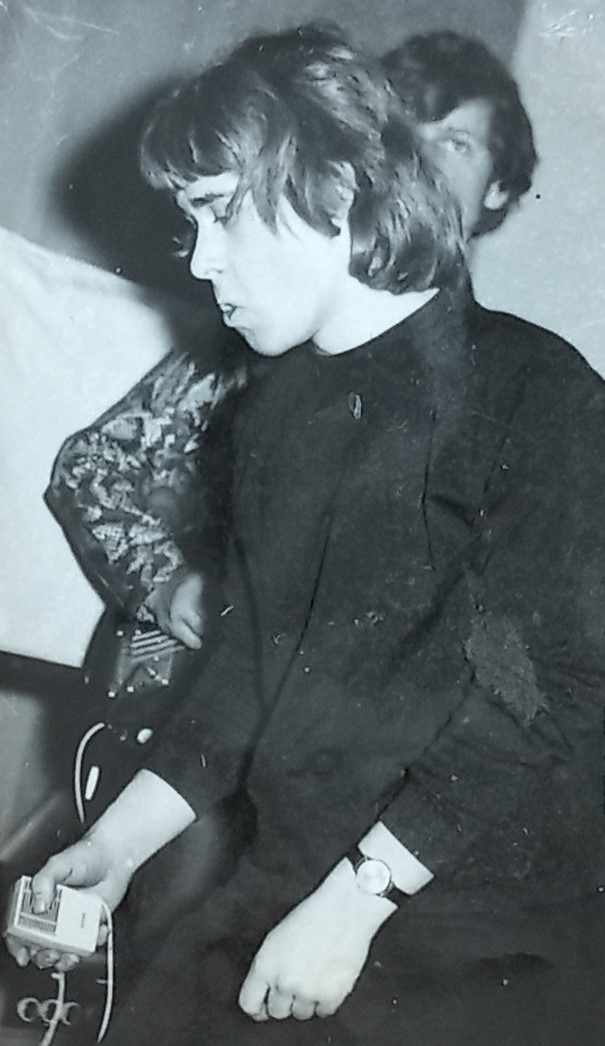

I was swinging between punk and underground, and secrets were after me

Download image

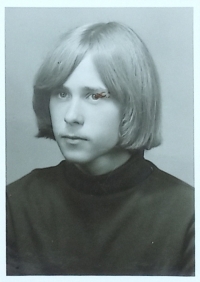

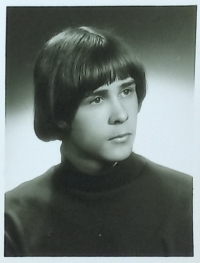

Milan “Fred” Pištěk, musician and cultural activist, was born on 15 January 1956 in Rumburk and spent his childhood in Šluknov and Benešov nad Ploučnicí. His mom worked as an accountant, and his father was an expert in the textile industry. As the witness himself says, his father was a classic 1968 guy. After the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops into Czechoslovakia, he lost his job as a production-technical assistant at the Benar textile company in Benešov nad Ploučnicí. It was clear to the family that Milan and his younger brother would not get into a good school. It was only thanks to acquaintances that the witness finally got into the secondary technical school of construction in Děčín, majoring in water management. However, he was kicked out of school due to a drunken accident just before graduation. Since elementary school, the witness was attracted to music, especially that which defied the regime. He wore his hair long and dressed in what was popular among the underground youth. After being expelled from school, he joined the army, fell ill and was given a two-year deferment after three months. In the meantime, he became the father of his daughter Beata and finished school. During his life, he often played in several bands at the same time, from dance orchestra to underground and punk. For several months in 1988, agents of State Security came after him. They had him in their records as a candidate for secret cooperation and gave him the code name “Ferda”. In 1989, shortly before the Velvet Revolution, he told the agents that he would no longer associate with them, even if they wanted to lock him up. After the November coup, he became an important figure in the cultural life of the Ústí nad Labem region. He founded the music magazine Scene Report and organized concerts and festivals. He was also at the founding of the RadioClub in Ústí nad Labem. He co-founded the association Ústí cultural platform 98, which has been organizing the Sudetenland Festival with other organizations since 2010. He also devoted himself to Czech-German exhibition projects representing the underground phenomenon in the Ústí nad Labem region or the defunct municipalities of northern Polabí. In 2022, the witness lived in Ústí nad Labem. We were able to record the story of the witness thanks to the support of the city of Ústí nad Labem.