The dictatorship remained, the people changed

Download image

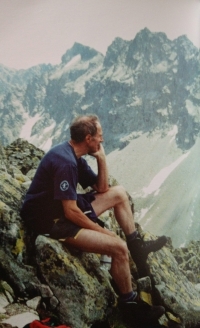

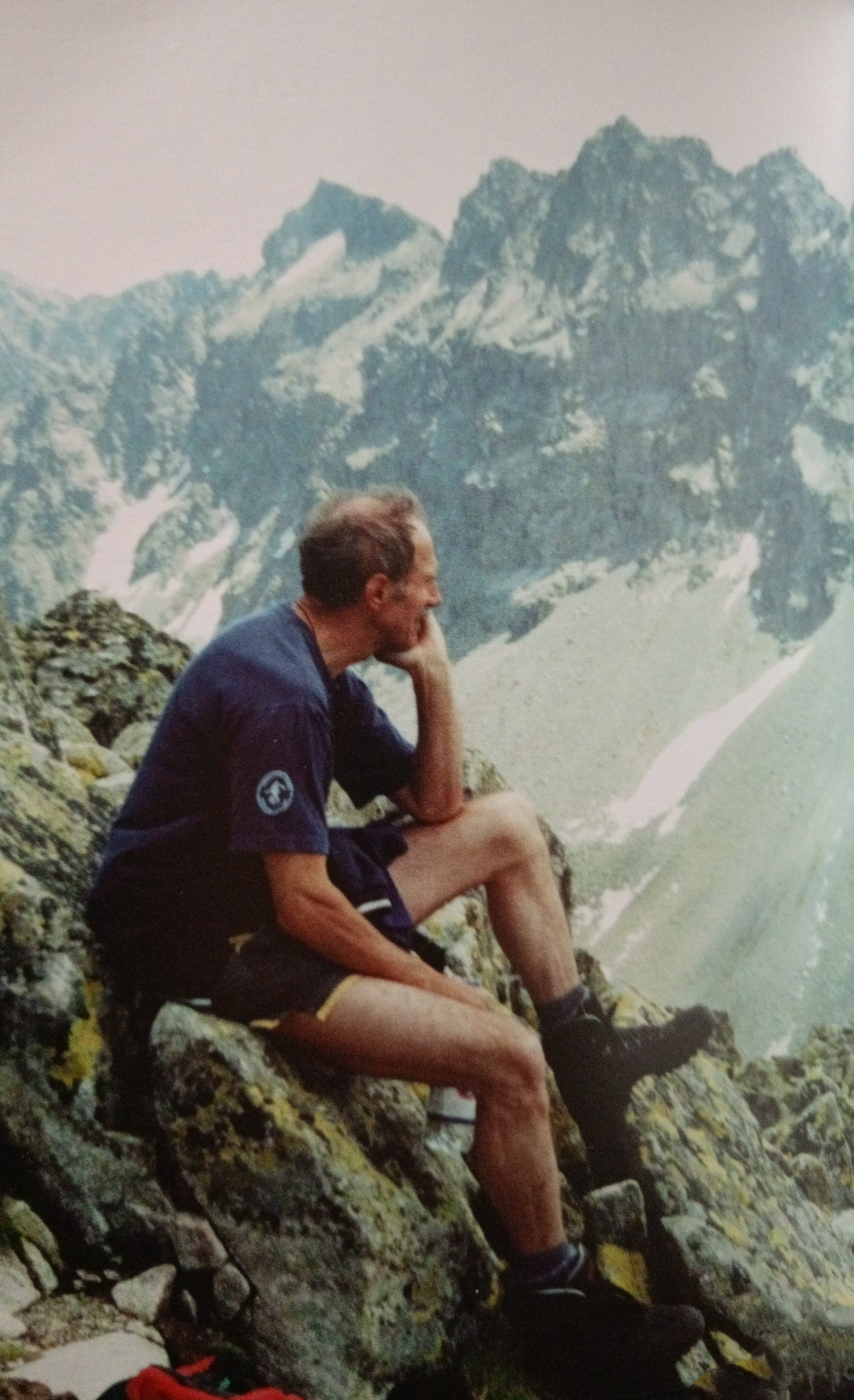

Peter Petras was born on 16 August 1946 in Kežmarok, the second youngest of seven children. His mother Žofia was the sister of Pavel Čarnogurský, a former member of the Slovak Parliament, and his father Jakub was a wine retailer, at one time the monopoly supplier of mass wine for the Spišská chapter. After the communist takeover in 1948, his father was arrested on the basis of a denunciation for collaboration with the Banderovci and spent four years in pre-trial detention. This meant hard times for the family, all the children had to help support the family. Peter Petras first graduated from the secondary pedagogical school in Levoč, worked as a tutor at a boarding school, and many years later extended his education in philosophy, earning his doctorate in 1986. Like his elder brothers Jozef and Ivan, Peter Petras worked as a mountain porter in the High Tatras. In 1989, he and his fellow teachers became one of the leading figures of the revolutionary movement in Kežmarok - in addition to putting up posters, they toured schools and businesses, urging participation in the nationwide strike planned for 27 November 1989. He helped to organise a rally in Kežmarok Square, attended by four thousand people, and moderated the speeches of the individual speakers. Later he also participated in meetings of the VPN (Public against Violence), played a role in the handover of power in Kežmarok and in the organisation of the first democratic elections. He refused to stand as a candidate himself. In 1997, he began the restoration of the then ruined and dilapidated Rainer’s Chalet, the oldest mountain chalet in the High Tatras. He repaired the hut at his own expense, thus saving it, and created a small museum of bearers. In 2023 he continued to work as a hut keeper and bearer.