The top secret police officers were unlikely to be affected by any cleansing

Download image

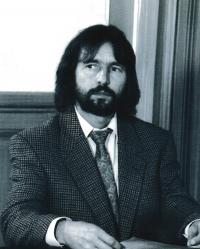

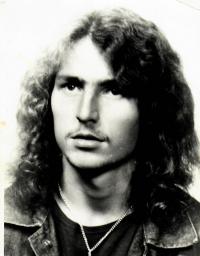

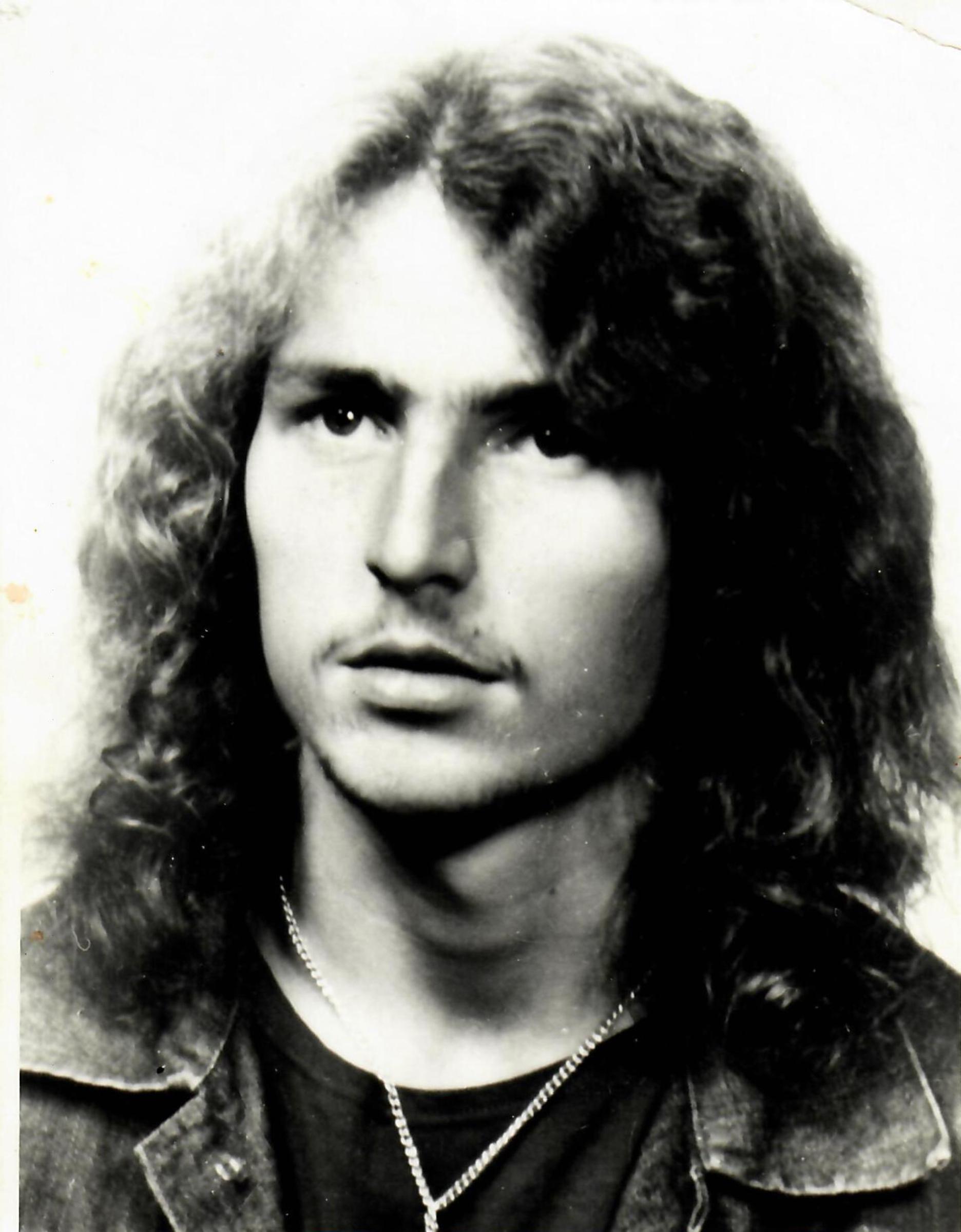

Karel Petráň was built on May 19, 1957, in Planá near Mariánské Lázně, since his childhood he has lived in Svojšín, in the Sudeten part of the West Bohemia, where his parents moved after the war to work. His mother worked in the agricultural cooperative, his father in the Svojšín mine. As a child he served as a minister in the Svojšín churn, took interest in religious faith and formed his own opinion about the totalitarian regime to which he refused to surrender. He moved in the circles of independent music and spread among the fans punk and foreign music. He trained as an electrician, had a family after the military service, helped the chartists to distribute Infochs and became a member of the Jazz Section, whose activities he transferred from Prague to Tachov region. He organised around himself people of similar outlook, organised concerts of semi-illegal bands and even established his own formation in which he played the guitar. He tried to return young people into the church through big beat music. In the late 1980s he regularly attended anti-regime demonstrations and signed Charter 77. When he wanted to join actively the activities of the Committee for the Protection of Unjustly Prosecuted (VONS), he was interrogated by the Secret Police and it was offered to him to become an informer, which he refused. In the revolutionary time of 1989 he established the Civic Forums in the Tachov region. In 1990, he was a member of the civilian commission which carried out cleansing in the police. He joined the Christian-Democratic Union and served on its national committee in 1992. After the merger with Civic Democratic Party (ODS) he left the party and took part in the local political live in his birthplace. He became the mayor of Svojšín in 2003.