If I didn’t see a way out, I wouldn’t get involved

Download image

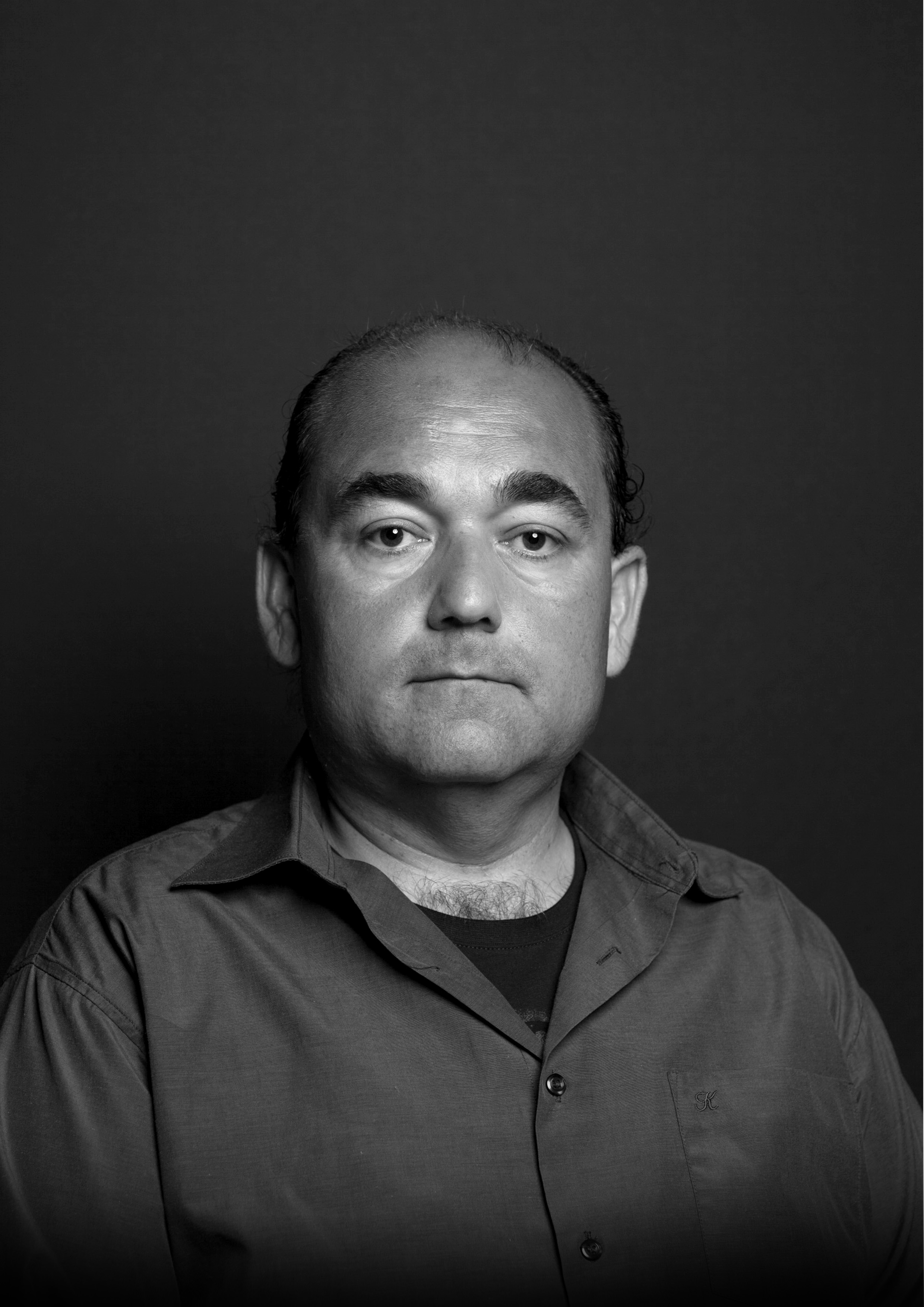

Branislav Oláh comes from Detva. He was born on 13 August 1974. He has eight older siblings. His father’s name was Ladislav, his mother Agnesa. His maternal grandfather was interned in a labour camp in Ilava and Hanušovce nad Topľou. Branislav’s father was active in a partisan group and with his brothers they took part in the Slovak National Uprising. Two of them were probably in the Mauthausen camp. The witnesses’ father was one of the members of the Union of Gypsies - Roma in Slovakia. Branislav attended primary school in Detva from 1980 to 1988. From 1988 to 1992 he studied at the Secondary Vocational School of Mechanical Engineering in Detva, majoring in the field of metallurgical materials as a storage operator. At school, he organized his classmates to protest during the Velvet Revolution in Zvolen, which they also took participated in. After the fall of the regime, he had jobs, mostly in the construction industry. In 2000 he became a journalist at the newspaper Roma New Letter, and later a blogger. He writes books about the Second World War and the Roma Holocaust. He collaborates with the civic association In Minorita on the project Ma bisteren! (Don’t forget!). Since 2006 he has also been working as a field social worker. In 2021 he is still working and living in Detva.