That era was horrible, but it couldn’t prevent me from trying to live my life to the fullest

Download image

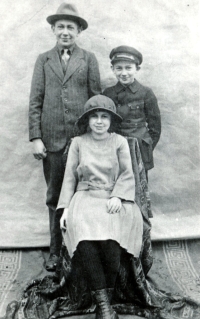

Eva Novotná, née Machová, was born on 2 December 1933 in Kyšperk (now Letohrad) at the foothills of the Orlické Mountains. After the Munich Agreement’s signing and the Czechoslovak border area secession, her hometown found itself in the immediate vicinity of the border. As a child, she experienced the situation primarily through her loved ones, perceiving their well-founded fears of the future. She also remembers other events related to the German occupation, the situation in the town at the end of the war, and the subsequent expulsion of the German population and its consequences. Shortly after the war, she began studying at the grammar school in Kostelec nad Orlicí, and in 1950, she changed over to the pedagogical grammar school in Hradec Králové, hoping that after graduation she would be able to continue her studies at university. She was finally accepted to study at the Faculty of Education after a year’s work experience in one of the displaced border villages in the Orlické Mountains. After graduation, she moved to Prague, started teaching, married, and had children. She describes the many hardships of everyday life under real socialism, but also the hope that accompanied the so-called Prague Spring and the subsequent shock after the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968. After her political screening interview, she had to leave school because of her disapproval of the invasion and soon decided to leave education altogether. In 1977, she started working at the National Library, and until 1989, she worked as head of the audiovisual center, and after the Velvet Revolution, as head of the public relations department. She participated in the transformation of the National Library into a modern institution. She hosted author broadcasts on Czech Radio for several years, taught at the Higher School of Informatics, and cooperated with the Writers’ Association. At the time of the interview for Memory of the Nations (2023), she lived alternately in Prague and Letohrad and continued to write articles for various periodicals focused on the reflection of contemporary events.