Look at all the things going on today – and that’s in a time of peace

Download image

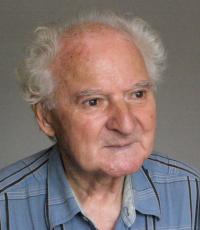

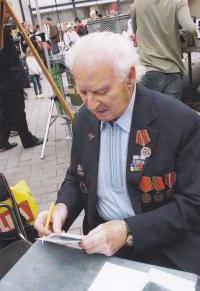

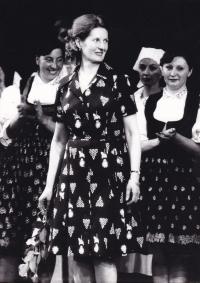

Ján Novenko was born on 5 August 1929 in the settlement of Kurtáň near Fiľakov in southern Slovakia; his father was a Russian soldier. In 1937 he enrolled at a Slovak school that was closed immediately after the occupation. In 1938 he started attending a Hungarian school. Schools were closed down in spring 1944, and the witness was sent to work in a German factory and later in a quarry. In 1944 his father joined the resistance movement, he helped partisans and observed the events of the Slovak National Revolt and the arrival of Vlasov’s Army. When the front passed through their region in late 1944, Ján Novenko joined the Red Army and functioned as a member of the Smersh counter-intelligence group. He participated in the Bratislava-Břeclav operation, he helped liberate Lanžhot, Hustopeč, and other places. In June 1945 he was released from the army; he returned to Slovakia, where he found employment while continuing his studies. In 1947 and 1948 he took part in the Democratic Youth Congress and Agricultural Exposition in Prague as a member of a folk dance troupe. He applied successfully to the Folk Dance Group and moved to Bohemia. In 1950 he married the singer Věra Novenková. His wife gave birth to their three children between the years 1952 and 1962. In 1963 Ján Novenko graduated from choreography at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague and became a popular and respected choreographer. He collaborated with many dance troupes. In the 1970s he met Jan Kobzík, a doctor and the founder of the dance group Břeclavan. In the year 2000 he and his wife moved in with their daughter in Moravská Nová Ves near Břeclav. He died on July 15, 2024.