We were brought up knowing that our parents may end up in prison at some point and that there were things, which were worth it

Download image

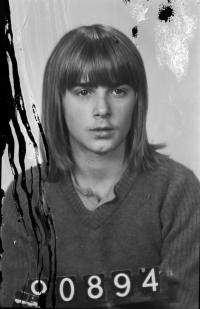

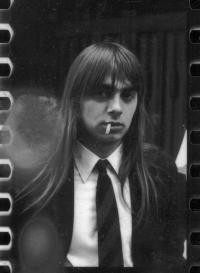

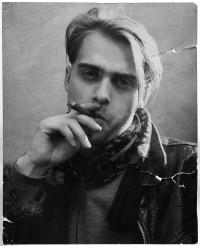

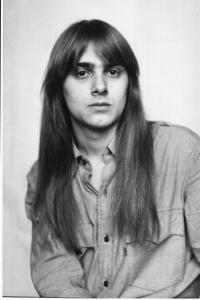

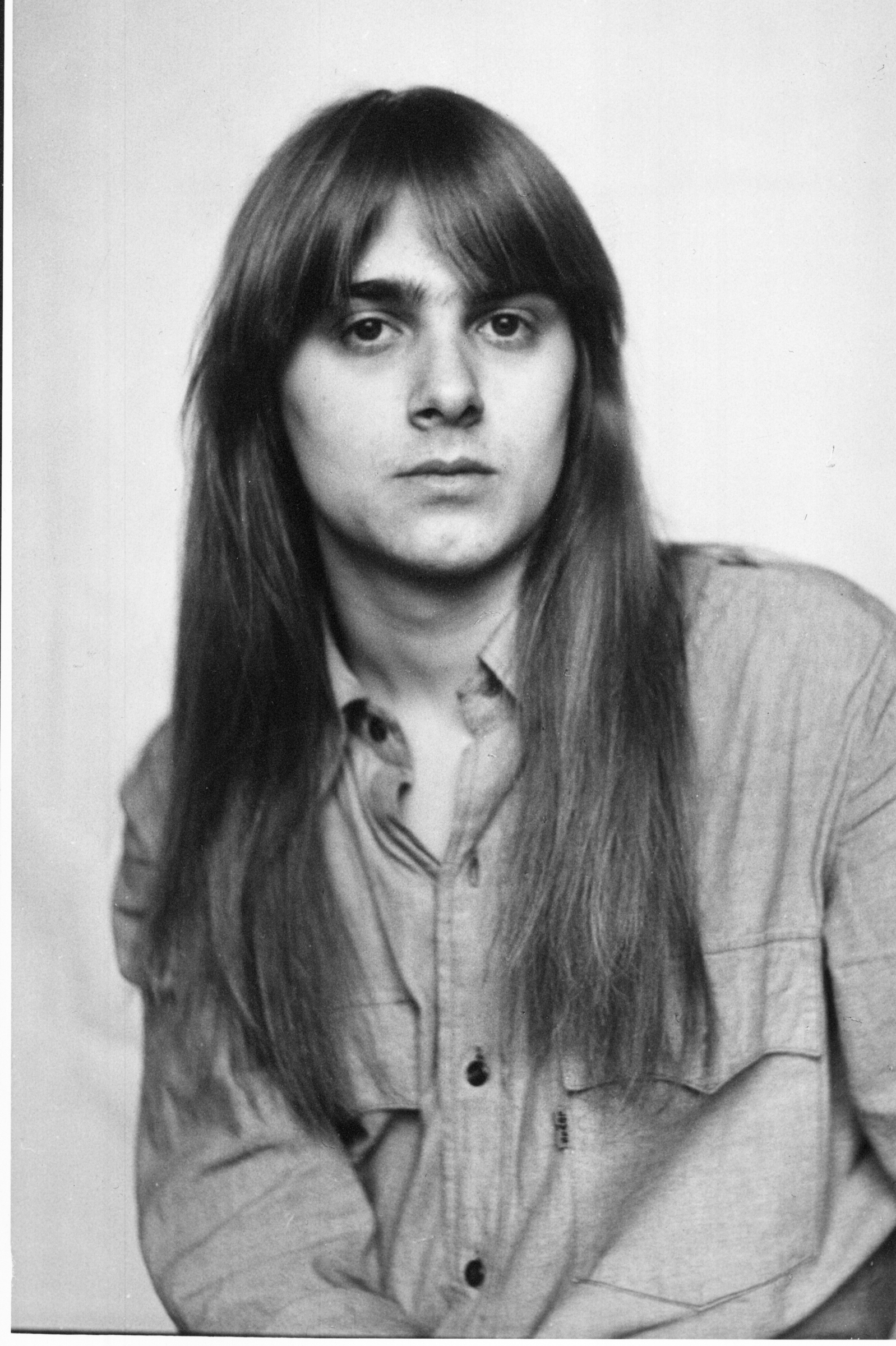

Ondřej Němec was born on 27 February 1960 into the family of Dana and Jiří Němec. Their apartment in Prague’s Ječná street served as a gathering space for dissidents, people from the underground and other anticommunists. The family left the country for Austria in 1968 but after a few months returned to Czechoslovakia where they felt they had their mission. All of the family members including children were under surveillance by the secret police; interrogations were taking place regularly. Ondřej faced interrogation for the first time while still a minor in 1977, following the funeral of Prof. Jan Patočka, and then for a number of times up until the Velvet Revolution. After the creation of the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Prosecuted, both of his parents were imprisoned and the seven siblings (of whom two were still minors) had to take care for themselves. Since twelve years of age, Ondřej has been doing photography, documenting some of the key dissident figures and events. His photos were included in samizdat publications, which he also distributed, despite never being allowed to study photography for political reasons. He trained to be a printmaker. Since 1975, he studied a vocational school associated with a cartography factory, where he then worked up until 1985. Between 1986 and 1990, he worked as a stoker in the Metrostav company. Following the Velvet Revolution, he worked as a photo reporter in Lidové noviny. In 2012, he left for Václav Havel Library where he still works in the archive of photography. Most of the negatives of his underground era photos were destroyed during the 2002 floods.