To live in a way that I never have to be ashamed of myself

Download image

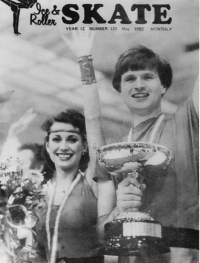

Anna Musilová was born on 11 March in 1933. Her family situation was very complicated; she was born to a single mother named Marie Táborská, who, after her divorce and birth of her child, was not accepted by her adopted parents. Five years of her childhood were spent at the start of the war, and she talks about this period lovingly, she experienced life in the Dagmar Orphanage in Brno until her mother was able to secure an apartment and bring her daughter home with her. She spent the later war years in Brno. Her and her mother moved often, and had lots of luck in many places, including fleeing multiple times from bomb raids. After the war in 1946 she was part of a group of children invited to Switzerland for an extended spa stay. After returning, she had her first meeting with her father, Richard Svaček, a factory worker from Hranice na Moravě, who had till then never reached out to contact her. She saw the postwar 1950s as a positive period of enthusiasm and building a new life. She started to work at fifteen years old, and following Gottawald’s call for those working in administration to transfer to production and manufacturing, she left her position as a main controller to work in a paper mill. In 1953 she got married; within a year her and her husband had a daughter, and then a son two years later. In 1961, while working at a military airport, she joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. The last twelve years before her retirement were spent as the head of the company club at the Vlněna factory in Brno. Both of her children took up figure skating very early. Her son, along with Anna Pisánská, fought their way to the top of the discipline of pair dancing. In 1980, they both decided not to return from competitions they had in London. As a result, the witness’s husband, Josef Musil, was persecuted; he had to give up his post in the Adam Machine Works for manual labor, building roads. In 1991 the Musil family had their house in Hranice na Moravě restituted, in which they decided to open a gallery. To this day, the witness has organized more than 250 exhibitions of regional artists-amateurs, countless concerts, and meetings with interesting people from the region. The M+M Gallery is a treasure for the city of Hranice na Moravě.