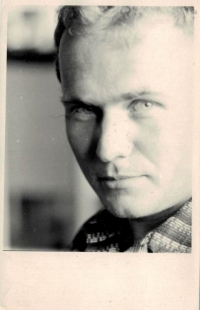

Stanislav Měřínský

* 1943 †︎ 2022

-

"I used to live in the Na pěšinkách area which was inhabited by army officers. For example, every afternoon, they would test the alarms. It rang in all those houses, everyone knew it was 5 pm, it's a test. When it sounded in August [1968], it was worse. Messengers were running, jeeps drove to pick the officers home and take them to the barracks. I'm not sure if I should brag about this but I had a lady visitor in my tiny apartment. We had a radio behind our heads and they said there, stay at your receivers, wake up your neighbours, wake up your acquaintances, the Czechoslovak Radio will announce special news. And she started crying, 'there'll be a war." I said: 'Don't worry, more likely some politician died. In Tábor, there were headquarters of the western army circuit, two large barracks. If there was a war, we'd already rest upon high. Something would explode here and we'd be dead on the spot. Then, when they announced it, she said: 'I have to go home, my husband is at the barracks and he'll be worried. He'll come home running and I have to be at home."

-

"As I said that there were all sorts of organisations legally allowed, including the Boy Scouts, those were these clubs. And we enjoyed it until the last drop. We had a travel agency which, until August [1968] organised fifty bus trips to Austria. So many people went for a trip! One could go only with an invitation, it was not possible otherwise, but some youth organisation in Stockerau, here before Vienna, gave us a pile of invitations, one only need to enter a date. Then we need to get entry permit at the Austrian embassy. There were queues, we always sent there some lady who would stand there all night. Everyone got five dollars and that was it. Because one had an invitation and it was supposed that the hosts would care for one. But, everyone who went there had some money hidden in their shoes or socks. So, this was a laudable activity, people could see that across the border, life is quite different."

-

"People did not get it. They did not want those dry wines. Or so I think. So there was Jihočeské zámecké [South-Bohemian Chateau Maison], in Prague, they had Pražský výběr [Prague's Select]. I wouldn't bring myself to swallowing it today. Those were such sweet lemonades. It had alcohol content, yes. Otherwise, those were abominations. The interesting thing was, in the Ostrava region, they wanted the miners to drink less hard liquors, vodka, rum... so a plant was built whose purpose was to teach them not to drink hard liquors and Ostravsky kahan [Mining Lamp of Ostrava] was produced there. It was still sweet but still... Wine has some 12-13 percent of alcohol and rum has 40 % so they were trying to save their health at least by a little bit."

-

Full recordings

-

Tábor, 26.07.2019

(audio)

duration: 01:10:42

-

Tábor - gymnázium, 26.07.2019

(audio)

duration: 01:10:42

-

Tábor - gymnázium, 26.07.2019

(audio)

duration: 01:10:42

Full recordings are available only for logged users.

The commies beat those children to pulp

Stanislav Měřínský was born on the 22th of February 1943 in Třebíč. His father Stanislav was a director of a dairy factory and when he was transferred to a similar post in Kyjov, the whole family moved. Only a year after the move, he was arrested for alleged crimes against property and sentenced for five years, which he served in the Jáchymov uranium mines. Mother of the witness, Jiřina, until then a housewife, needed to get a job, first in accounting, then she worked at the post office. Stanislav was not admitted to a high school despite his excellent grades. He worked in a vineyard for a year and then he was admitted to School of Food Preservation in Bzenec. For family history reasons, there was no way he could think about getting tertiary level education. He was assigned a job at a food preservation plant in Tábor. He rose through the ranks and reached the position of production manager, he submitted over 50 innovation patents. In 1971, he got married, he and his wife raised two children. He lived through the events of 1968 and 1989 in T8bor, as he himself says, “with his ear on the radio speaker”. Stanislav Měřínský died on April 19, 2022.