I exchange bound Lenin for tied down Brezhnev

Download image

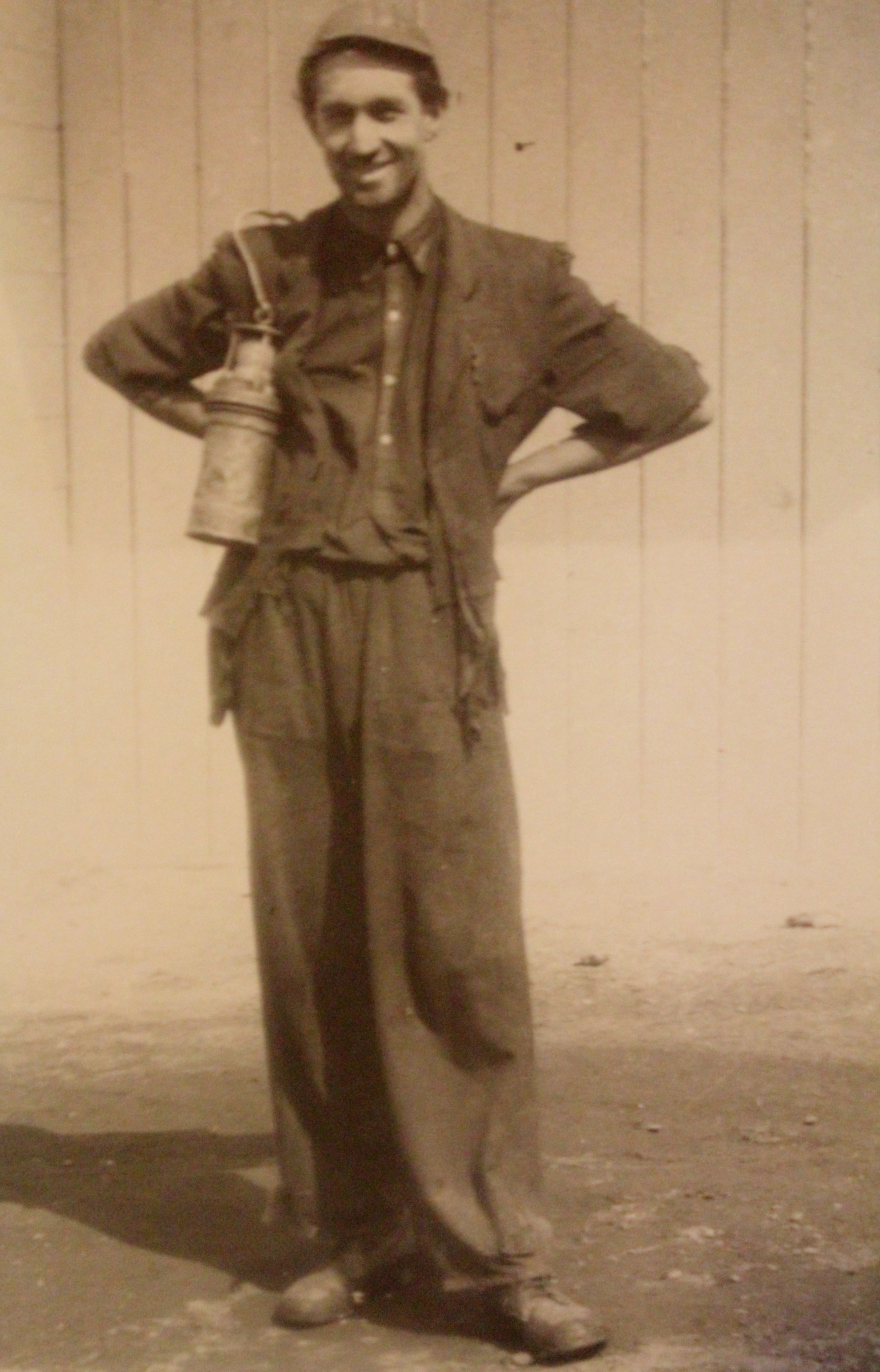

Jaroslav Mazura was born on May 18, 1935 in a farmer’s family who had traditionally worked on their lands in Slatina nad Zdobnicí for several generations. During WWII his father had to provide accommodation for German soldiers, and later for English and Soviet soldiers as well. The family spent the period of collectivization of farms under the pressure of officials who were persuading Jaroslav’s father to join the Unified Agricultural Cooperative. The pressure later intensified. Jaroslav and his brother were prohibited to study and Jaroslav eventually had to go to work in mines. An incident involving bullying conducted by a fellow worker - a member of the Communist Party - was followed by a court trial, which recognized the perpetrator guilty. This man then continued to harrass Jaroslav: he was sending him financial compensation together with threats written on the cheques. Jaroslav Mazura later worked as a keeper of breeding bulls in Kostelec nad Orlicí. He went through his military service in Slovakia, where he received a driver’s licence and where he also met his future wife. He spent most of his life working as a driver. Jaroslav became a widower and he later remarried.