We shot the red star into a thousand shards of evil. We’ll never find them all.

Download image

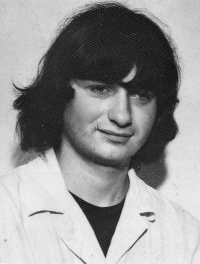

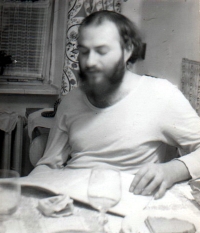

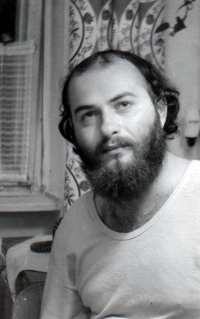

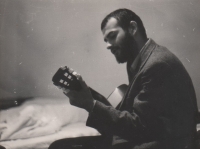

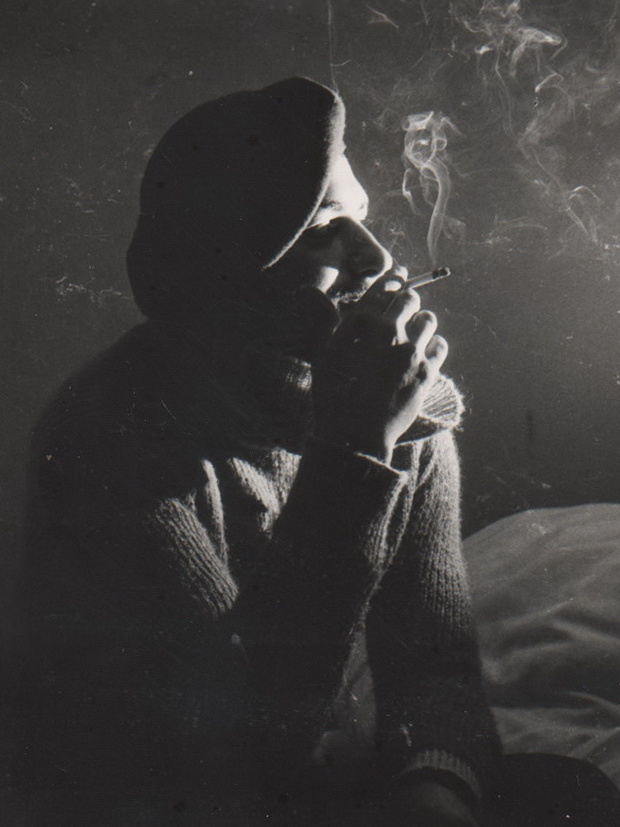

Luděk Marks was born on 11 November 1963 in Ústí nad Labem. His father, the landscape painter, and caricaturist Josef Marks, disagreed with the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968, for which he was forced to change his profession. He had to cease being a painter and he became an engine driver from one day to the next. When his mother, Marie Marksová, dressed in black on the anniversary of the invasion in 1969, the repression fell on her as well. Luděk’s father began to paint unofficially in a group associated with the academic painter Ladislav Lapáček. Together, they prepared Luděk for the Hollar School of Art. Luděk Marks started to have his first problems with State Security (StB) during his studies for repeatedly visiting Lennon’s Wall with his classmates. After graduating from high school in 1983, his path to university was closed. He wrote poetry and, after meeting Egon Bondy, joined the circle of underground literati meeting at the Klamovka restaurant. He was arrested and interrogated several times by State Security for his participation in demonstrations. He became editor of the underground magazine Vokno, where he worked until 1992. He worked at the Museum of Czech Literature and later at the Heritage Institute in Ústí nad Labem and the Institute of Monument Preservation and Archaeology in Most. He created an art gallery and opened a bookstore in a Cistercian baroque farmhouse in Vtelno near Most. He published two collections of poetry - The Shadow of the Candlestick and Over the Snake’s Skin. His lyrics have been made into music by David Koller and Vladimír Mišík. At the time of the interview in 2023, he was working as a documenter and technician in the archaeological department of the Ústí nad Labem City Museum and living in Teplice.