“In the end we agreed that we must go there, where our government needs us.”

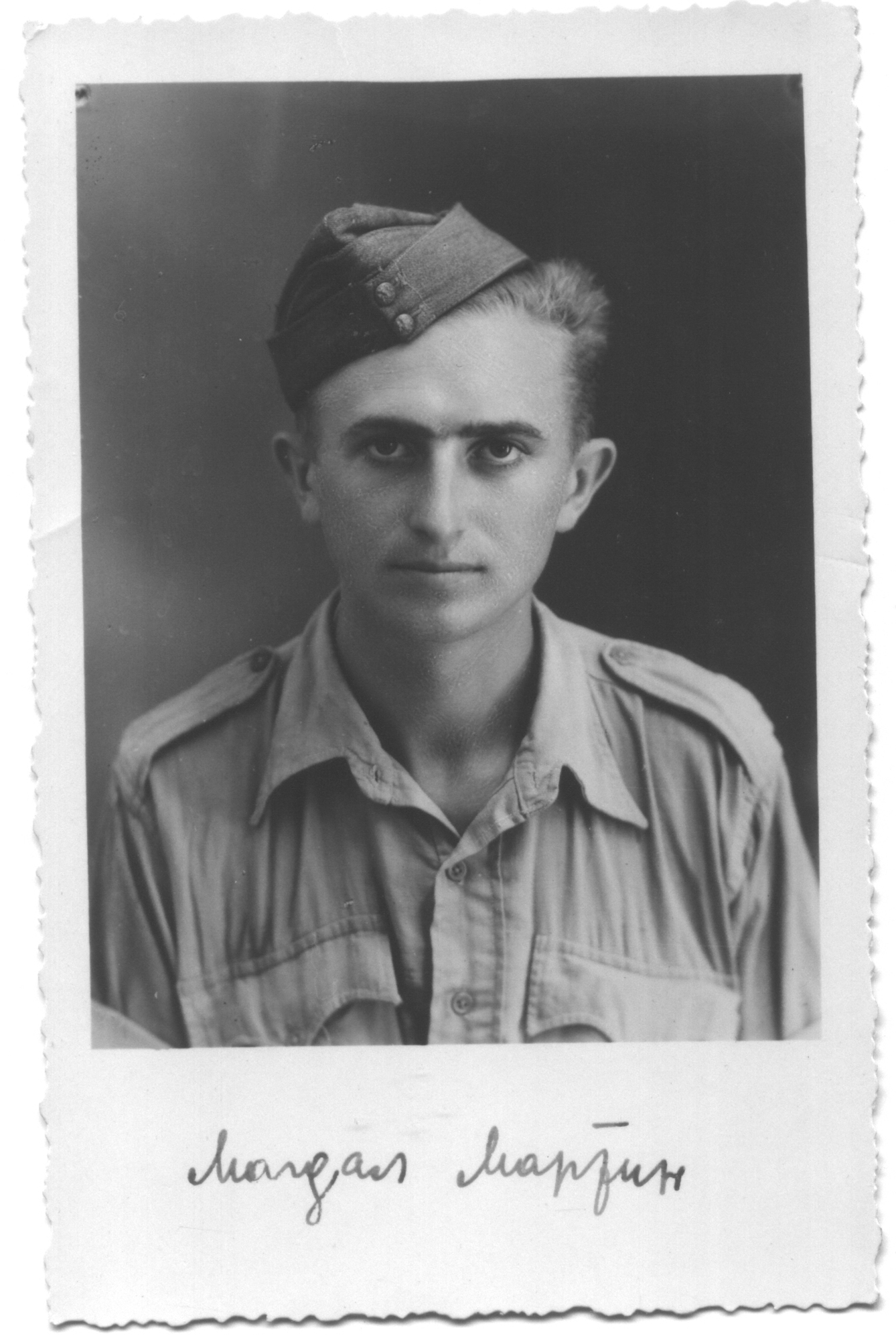

Martin Mahdal was born in 1918. He spent his childhood in Bánov, near Uherské Hradiště. In 1939, he left the Protectorate for Poland, where he joined the Polish Legion. While retreating to the east, he was captured by Soviet soldiers. He then became a member of the auxiliary corps of the Czechoslovak army in the Middle East, functioning among other things as a sapper. He travelled by boat to Britain. After the war, he worked in international trade.