One advantage of being imprisoned is when one prays and keeps one’s faith

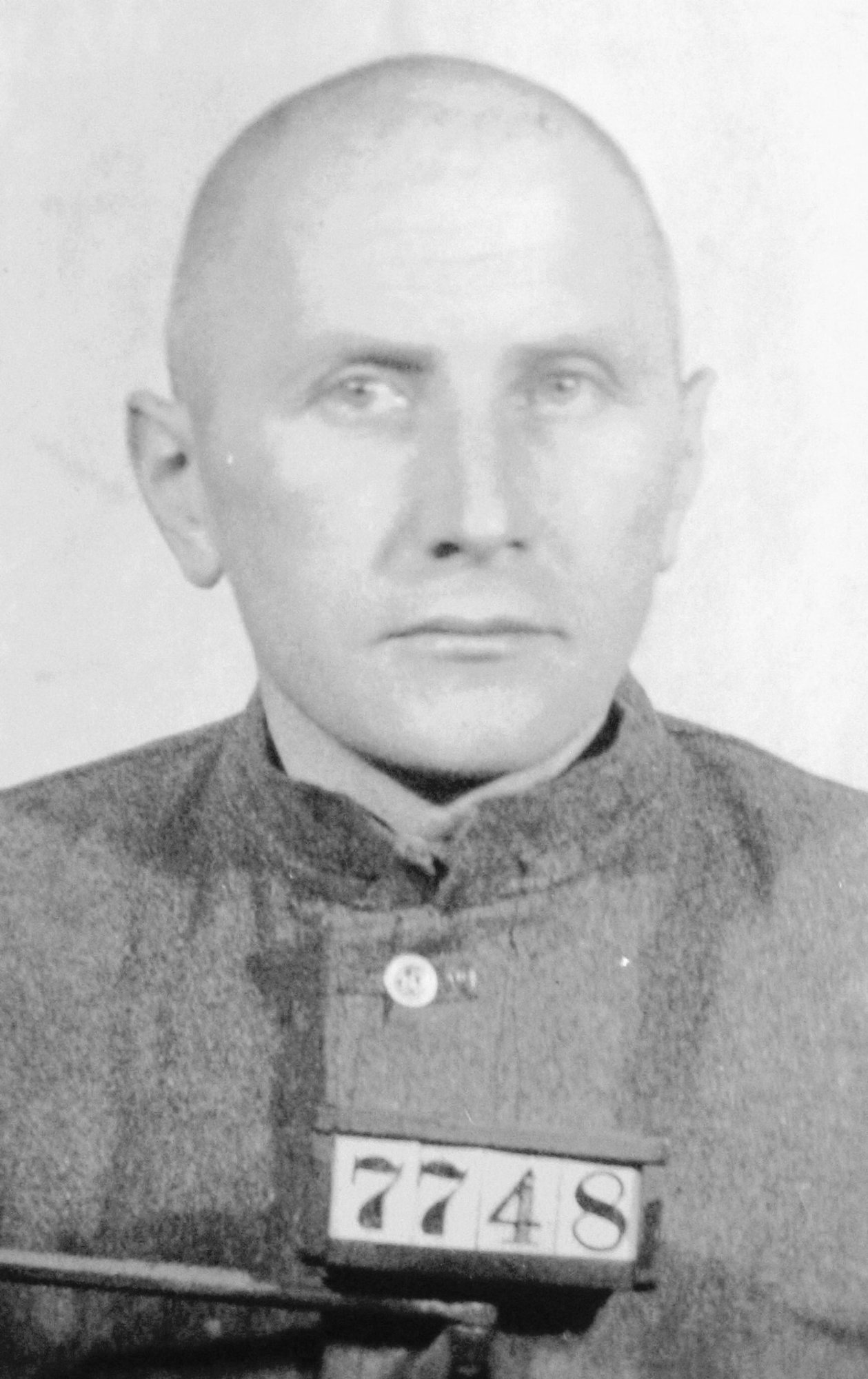

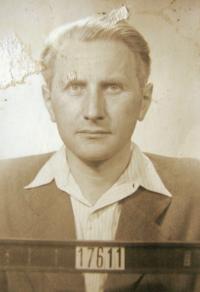

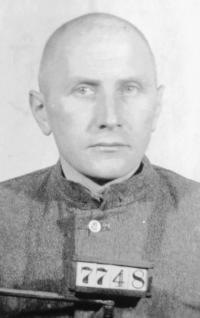

Jan Machač was born June 1st 1915 in Horní Lideč in the Vsetín district. His father Josef Machač was a miller by trade, and so little Jan was growing up in a mill. Later his father left the miller’s trade and began working as a railway worker. His mother Marie Machačová, b. Novosadová, was taking care of the household and raising five children. Jan Machač attended a lower elementary school in Horní Lideč, and during the higher elementary he walked several kilometers every day to nearby Valašské Klobúky; later he commuted by train. After a grammar school was opened in Vsetín, Jan Machač continued his studies there, and completed them in 1938. Since his childhood he has been considering a priest’s vocation. Eventually coincidence played a role in his decision, when he during one of his trips on train met a nun, who helped him with application to the theological faculty. Jan Machač began his studies of theology as a seminarian at the faculty, which was however closed soon after together with other universities and transferred to Dolní Břežany as an archiepiscopal college. Jan Machač completed his studies in 1943, when he was ordained by bishop Elkčner in the St Vitus cathedral. He celebrated his first mass in his native Lideč on June 6th 1943. After his ordination the first assignment was in Dolní Bělá near Manětín, where he spent one year as a chaplain. From there he was transferred to Pilsen, where he also witnessed the liberation of the city by American soldiers. There he experienced yet another significant event - he was the very first priest to welcome the spiritual director and future archbishop Beran, a returnee from a concentration camp, in the liberated homeland. From Pilsen, Jan Machač also made trips to borderland areas, where he celebrated masses for new Czech inhabitants. He was also assisting in solving troublesome situations arising from the deportation of German priests and the forced deportation of German population, an issue he felt very sad about. After one of his visits in Cheb he received a request to come to serve in this parish. This really happened in 1946 and Jan Machač then served as priest in Cheb for five years. He considers this time one the most beautiful and fruitful periods in his life. Already in Cheb Jan Machač clearly voiced his stance toward the people’s democratic regime after February 1948, refusing its atheistic ideology. In 1949, Roman Catholic priests were pressured not to read a pastoral letter from the bishops to their congregations, however, Jan Machač was not intimidated by the presence of several State Police agents in the church and he read the entire document together with his own notes. This act did not have immediate repercussions, but some time after the situation changed and on September 8th 1949 Father Machač was arrested and imprisoned. He refused to write a petition for pardon, and he was eventually released together with other priests on the state holiday on October 28th 1949. However, before long he was arrested for the second time, followed by a court trial and many years of imprisonment in communist labour camps and prisons. On November 30th 1951, Jan Machač attended a seminar held in the archiepiscopal seminary in Prague. There, he was arrested and detained in the Prague-Ruzyně prison. He was subjected to several interrogations, he suffered cold and hunger, and experienced repeated interruptions of sleep at nights. He admitted that towards the end of his detention he suspected some substance was being added into his meals and drinks. He drew his strength from his faith and regular prayers, which he was saying in front of a cross engraved into the wall of his solitary cell. He was accused of reading the “illegal” pastoral letter to the congregation in Cheb in 1949, and of organizing (as an administrator of the vicariate) a petition, in which he was collecting signatures of other priests against the law on economic funding of churches. He was also accused of failing to report the illegal stay of his chaplain Schützner on the Czech territory, although he was aware that this chaplain had crossed the state border illegally and then worked as an enemy agent in Czechoslovakia, attempting to cause harm to the people’s democratic regime. The trial with Jan Machač took place on August 7th 1952 in Prague. He was convicted of high treason and sentenced to seven years of penal servitude, loss of property and civil liberties in the duration of six years. During his seven-year imprisonment he was first held in Valdice, where he was also sent later from various other prisons and labour camps. He also spent some time in prisons in Mladá Boleslav, Pilsen, and in uranium labour camp in the Jáchymov region, from which he was for his pastoral activity transferred to the prison in Pilsen-Bory. After his release in 1958 Father Machač spent some recovery time, but immediately after he was ordered to start working in a worker’s profession. He was not accepted as a gardener nor a street-sweeper, and he eventually managed to find a job in furniture factory TON in Bystřice pod Hostýnem. There he worked with a circular saw for seven years before he was allowed to serve as a priest again in 1966. His first parish assignment was in Gottwaldov-Malenovice. In 1968 his service was requested by the Prague consistory, where he worked as a personal referent till 1971. A forced dismissal from the consistory eventually proved to be a blessing, because he was then assigned to the church of St Mathew in Prague, where he served for thirty-one years. He takes great joy in the fact that several present-day priests originally come from his congregations, and that during times, when churches elsewhere were experiencing significant decrease in believers, Father Machač´s church was always full of Catholic families with children. In 1998 he was awarded the honorable papal title monsignor, and when Father Machač looks back on his life, he certainly does not mention any regret about wasted years in communist prisons. He took it as a necessity, which had to be dealt with. He feels grateful for his priesthood, and he also tries to pass this life perspective to his followers. ´It’s been a nice life,´ he laconically concludes his narrative.