The hardest is when you have to leave home, and you don’t even know where and what you’re going to

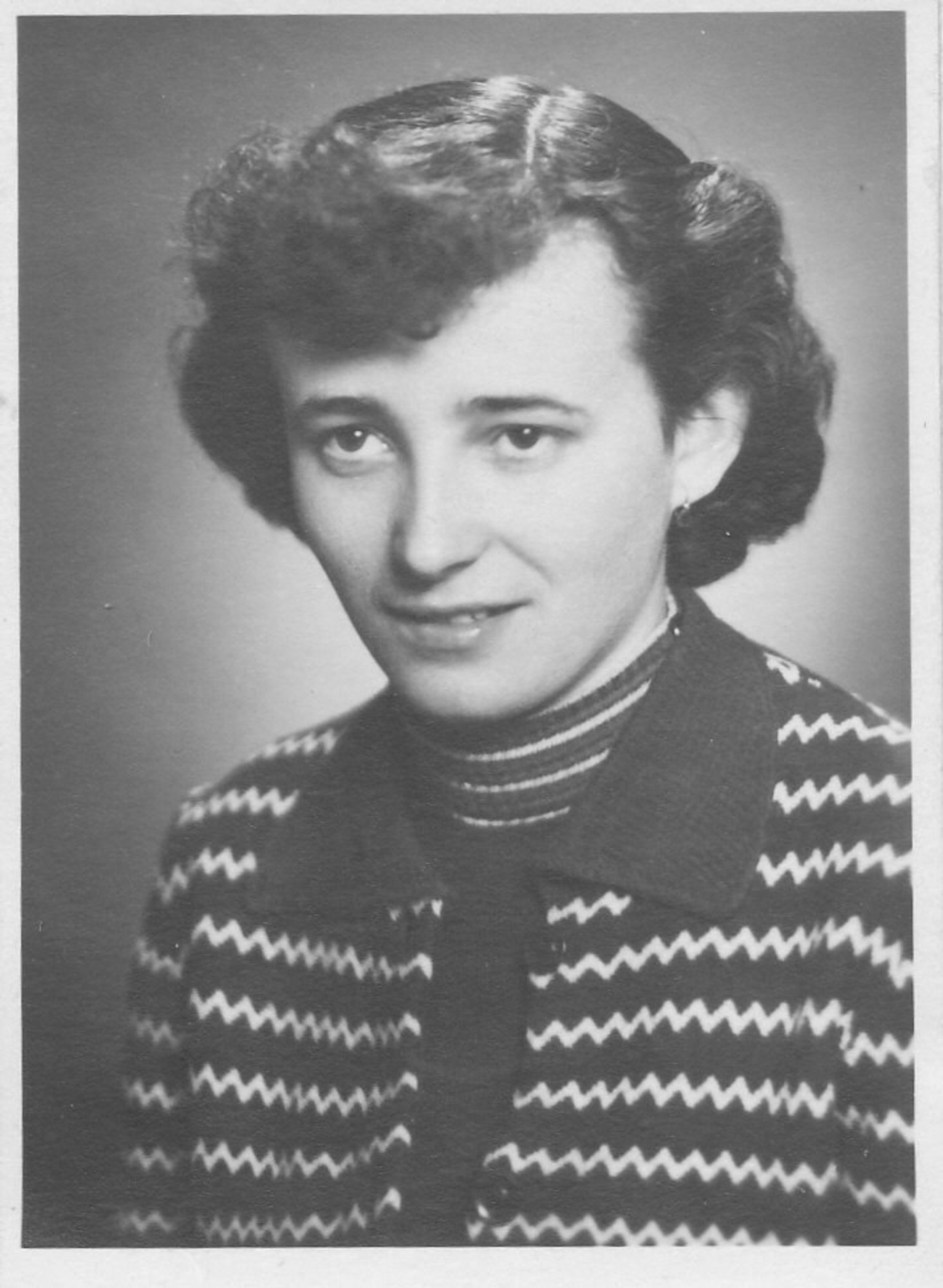

Anna Luzarová was born in 1935 in Frélichov to Růžena and Jan Slunský. She began attending a German school in Frélichov during World War II, after 1945 she continued at a Czech school. Her parents considered themselves Moravian Croats, they spoke Croatian at home. In 1949 Anna and her mother were deported to Hartmanice near Radkov, Opava District. There were several Croatian families there, and they tried to renew their original communal style of living. When Mrs Luzarová’s husband Boleslav had the opportunity to move to Kuřim in the 1960s, the family decided to return to souther Moravia. The Luzars had two children. Their grandchildren also profess their Moravian Croatian roots.