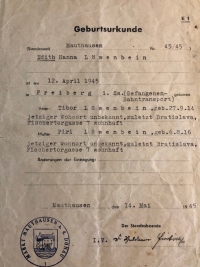

Hana Lomová (Löwenbein) Moran

* 1945

-

Well, well, you remembered that you learned a lot and you got those sixties and such echoes of the Prague Spring in Bratislava.

That was a little later. Sorry to interrupt, but talk.

Well, it was a little later. Yes, but as if, in the sixties when you graduated, you stayed in Bratislava and, and you were already more active, so that socially?

So, I still had a friend from Prešov and, Egon, who now lives in Belgium. We were supposed to get married, but we didn't get married. As if it wasn't. Egon introduced me, he was eight years older and he introduced me to Jewish society. He went to this group also. They were all Jewish students, not only from Bratislava, but mainly from Bratislava. And that's where we started meeting. Egon and I then broke up, but I kept going there, so it was my company.

And in which year was it?

It was in thirty-six.

And what is the name of Egon, I think a surname?

Well, I have to write it to you. This is so complicated.

Well, OK.

And the second person was Paľo Kučera. We were meeting in his flat. And Paľo.

I know him.

Well, Paľo is so good person. We were meeting in his flat, we loved his mom, well. She was our mother and she said that we were her children. So greet him when you see him. I'm still in touch with him. With Paľko. So he can tell you then, and Hana she was. Everyone laughed at me, I was the smallest and youngest. Do you know? And I was scared, even though I was, even though I had lived in Bratislava before. And so, that was my company. They took me to the Jewish kitchen, to the Canteen. And you know, that's how they taught me about the holidays. However, I am, you know my mother, because she did not want to attract attention as a Jew. We had a beautiful tree every Christmas. We did not celebrate Jewish holidays at all, I did not know what Jewish holidays mean. What made me sad, but I said to myself, it probably hurts her because it reminds her of her parents. So I was quiet. And then in Bratislava, in the company of Kučera, we were there. I met adorable people there, and they taught me. That was the first time I celebrated Chanukah. I didn't know anything. And so I was happy, you can't even imagine it.

-

That was the moment they were in transport, it was the last one?

From Sereď to Auschwitz, from Sereď to Auschwitz. They were in Sereď one day and then they drove them to other trains, you know the wagons. They continued on to Auschwitz.

And your mom and dad went to Auschwitz, still together?

They were still together in that wagon.

And.

When they got there they divided the men and women.

And that was the last time they saw each other?

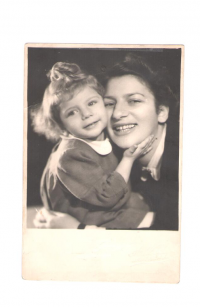

One week later, they saw each other again. Mom was already shaved, you know. And she had the one, the coat, the coat dress, luckily, so big, that was good. And they saw each other through the wire and my mother told me, and I, I'll never forget that. Pirečko, think only of good things, it will be fine. Just think of good things. And that's what Mom lived. Do you understand? She told me that whatever happened next. You know, two weeks after she reached Auschwitz, she was on a transport to Germany, where they were going to those barracks and worked in an aircraft factory from which no aircraft had ever flown. There she stood, riveted wings, you know she stood, twelve, fourteen hours a day, they didn't eat much. But all the time she went, you know the women were marching, in the streets, and the people in Freiberg were standing there on the street, on the sidewalks, looking at the women. And my mom said, I was just looking at those German kids because I wanted you to be a blonde, a blue-eyed blonde. The poor father had blue eyes and mother was dark, you know, a very pretty woman, dark, dark, so brown, brown. And the face, the dark eyes, she was pretty. And she said I want to have a blonde kid and she knew it was going to be a girl. That's if my mom made a point, it was like that. And so, and you know how she says it, it was her mantra, it was hers, except that Šmajsrajel prayed every day, that Hebrew prayer. And then she said I want to have a girl, her name would be Hanka. Her name will be Hanka. She already had the name, everything was arranged. She fixed it, you know it, with the power over us.

-

So, you know, the Russians were coming on one side, the Americans on the other, and the Germans already knew they wouldn't have a great future. And so on the fourteenth, the commander came to the barracks and said to all women, "Prepare for going, we leave." My mother and thirty women were pushed into one, and with me, they were pushed into one, into one truck. What I was wearing was a shirt and a cap that the prisoners made for me. At that time before that lady started screaming, until I was born. So, by the way, I donated that blouse and that cap to U.S The Holocaust Museum, in Washington, it is there. And so, in that car, you know, they were supposed to take them to the woods, but already, Mom says, we've heard the gunfire, the front was so close that the truck turned with them and came back to the station in Freiberg. And they loaded the thirty women into one wagon, the same women. And my mother said that when the other women saw it, they started screaming because they were happy to know that the Russians were so close. Well, now the journey has begun. And that train journey lasted from April 14, forty-five, to April 29, forty-five. Other trains joined in, because the Americans had already bombed those, those, railroads. And on April 21, the train stopped in a town called Horní Bříza, in the Czech Republic near Plzeň. And there, he had to stop because the rails had been bombed before, you know. And people heard, especially the gentleman who took care of the station, heard that I was crying. And they, because my mother didn't have much milk and had me in her, in her, whatever she was wearing. And in the meantime, a boy was born on April 28, I told you there were three mothers, and one Polish mother was giving birth on the train. Well, when the commander of the railway heard the cry, he went to the train commander and told him that if they allowed him to feed the prisoners, the prisoners, he would feed the soldiers.

-

Full recordings

-

Zoom, 04.11.2020

(audio)

duration: 02:44:30

Full recordings are available only for logged users.

“My mom grabbed your mom’s hand because when Mengele asked who was pregnant and your mom wanted to move, my mom stopped her.”

Hana Lomová was born on April 12, 1945 in Germany, near Drážďany, specifically in Freiberg. It was a satellite camp in Rosenberg, where her mother was imprisoned at that time and worked in an aircraft factory. She was born in very inhumane conditions, on a board in a factory.

Hana comes from a family where both of her parents had Jewish roots. Hana’s mother, who was already married, was called Piri Löwenbein, then Rónová and after the war changed her surname to Lomová. She was born in Stropkov and later lived with her parents in Zlaté Moravce. Piri met the memorial’s father, Tibor Löwenbein, in 1941 while studying in Bratislava. He worked there as a journalist for a local Jewish newspaper. They were taken to the Sereď detention camp on September 28, 1944. At that time, Hana’s mother was already pregnant. The last time she saw her husband after being taken to Auschwitz, and then just only she was taken to Germany, after this she had no news about him. Tibor died on the death march to Glovice. Piri and Hana managed the death march. The journey by train lasted from April 14, 1945 until April 29, 1945. They were liberated 5.May, by the American army from the Mauthausen camp.

Hana finished primary school and grammar school in Prešov, where she and her mother had to move from Bratislava after finding out of Hana’s asthma. She was admitted to the university, SVŠT- Faculty of Chemistry in Bratislava, in 1962. She graduated in 1967. During university, Hana experienced a very special fact, she could get to know her Jewish culture thanks to her friend Egon. She also became a member of the Communist Party, just like her mother.

The memorial was first married on October 21, 1967 to Jozef Berger, who had the same jewish origin. He was a chemist working at the academy and about eight years older. It was more racional wedding than love. On August 31, 1968, they left the Czechoslovak Republic due to the occupation at that time and emigrated to Israel, where Hana finally felt free. They remained living in Aždoba, where Hana gave birth to her only son, Tomas, on December 19, 1968. She never persuaded her mother to emigrate to them. Her husband Jozef was dissatisfied in Israel and decided to go to Germany in 1971. Hana followed him with her son a year later. She stayed there for several weeks and on April 12, 1972, she left. She would never accept the behavior of some German citizens. So, she was back in Israel, where she had to start from the beginning. She worked in a pharmaceutical company and later moved from the laboratory to the office, dealing with the legal approval of medicines.

In 1974, Hana married for the second time to a colleague from work who came from America. She lived with her American husband in Israel until 1977, until she completed her doctorate, and immediately afterwards, mainly because of the post doctorate, she went to America with him and her son Tomas. However, even this marriage did not last long and they broke up due to different interests. She married Mark’s current husband in 1990, while skiing in Vermont, and now it was a beautiful 30 years. She currently lives in California and is the grandmother of two beautiful grandchildren.