Man should be man to man

Download image

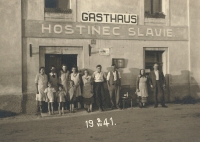

Karla Lierová was born on 29 June 1950 in a brewery in Kyjov. Her father, Karel, was a renowned brewer. Her grandfather from her mother’s side, Antonín Hnilica, owned a large farm. When the Communists came to power, the family suffered from persecutions because Antonín Hnilica refused to join the local united agricultural cooperative (UAC). Karla’s older sister Pavla was not allowed to attend secondary school, and her father was fired from his post as head brewer. Karla enrolled at the Secondary School of Education in Kroměříž in the 1960s, when the situation in society had generally relaxed. After graduating in 1969, she underwent political screenings and began working as a pre-school teacher in Hluk. Five years later she was appointed headmistress of the nursery school in Traplice, where she remained until her retirement in 2011. Her headmistress’s career required her to make numerous compromises with the ruling regime. But Karla never joined the Communist Party. A close friend of her mother, Marie Cichrová, was sentenced to 18 years in prison in the 1950s for charges that included providing lodging to the guide and courier agent Štěpán Gavenda (with her brother Jožka). Karla Lierová is thus one of the last witnesses of this story.