How the Communists gave God native-american features

Download image

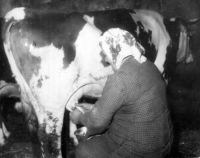

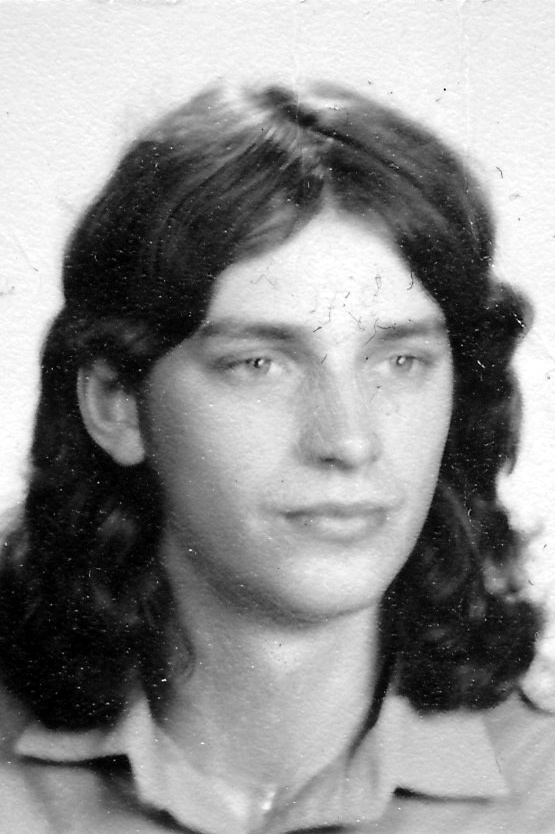

Václav Lebduška spent his youth in Závratec near Čáslav. His parents used to farm there, breeding horses and cattle. Under pressure, they joined a cooperative, of which their father was the chairman in the 1960s, and the village adopted the JZD as its own. The witness grew up in a landscape of disappearing traditional farming, attended mass in the Catholic parish, participated in illegal summer stays of the Salesian Order called “cottages”, and was part of a rural community resisting regime conventions. He was also a participant in the 1985 Velehrad pilgrimage. He served his compulsory military service in the Border Guard as a boilermaker and pig feeder. In 1987, he settled in Prague. He became an educator at a centre for troubled youth and joined the activities of the Prague Dissent. He printed and distributed the samizdat “Information about the Church” and participated in petitions for the release of political prisoners. In 2023, he lived in Pečky u Kolína and worked as the director of a children’s home.