The victims of the Holocaust are not victims of the Second World War, but they are victims of the mass murder of the civilian population, which could only have happened under the guise of a war turmoil

Download image

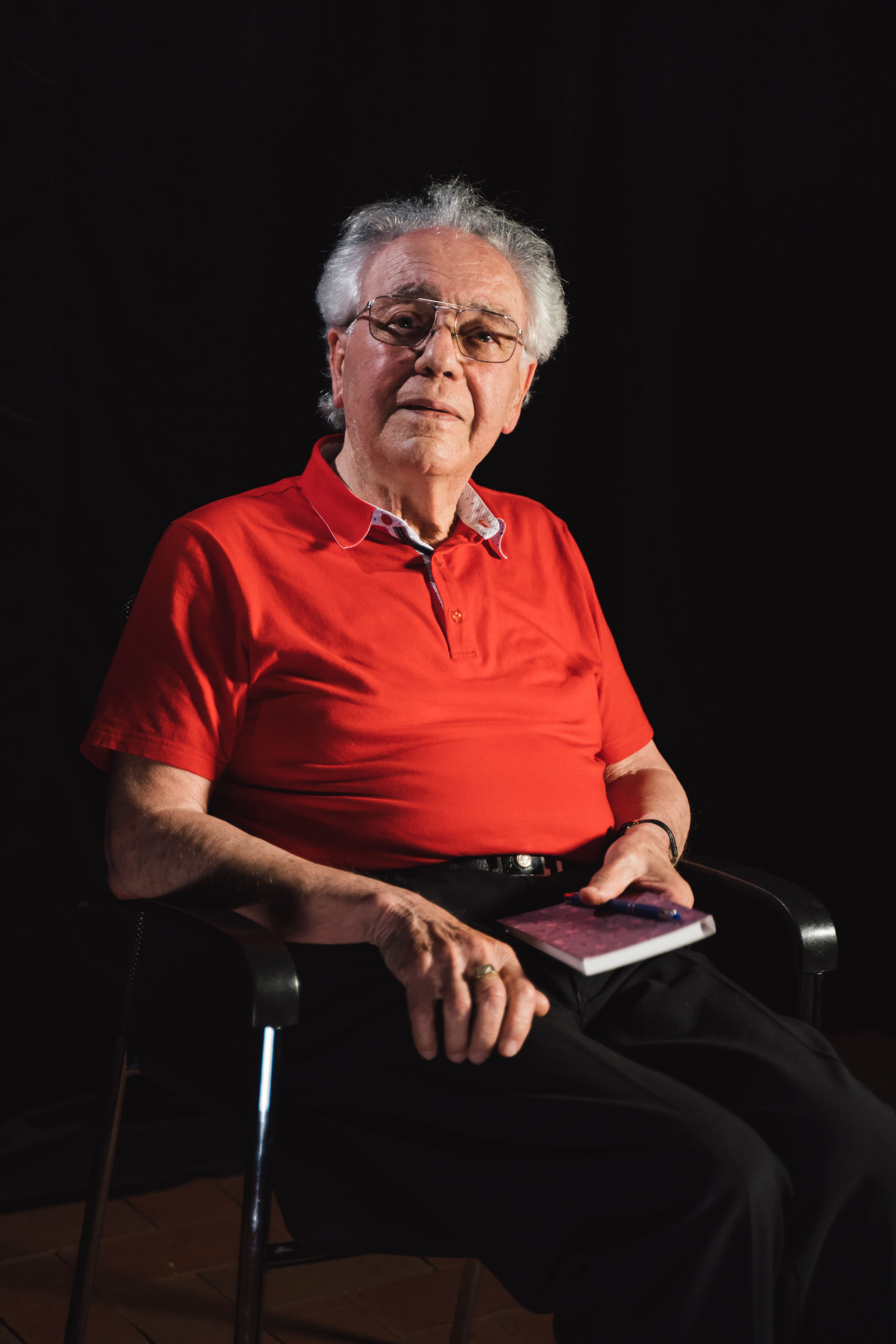

Tomáš Lang was born on 9 May 1942 in Budapest to parents of Jewish origin, Alexander Frankfurter and Hermine, nee. Lang. He lost both parents and his maternal and paternal grandparents during World War II. After the war, his mother’s sister, Aranka, took him from the hospital where he had been hospitalized during the deportation of Jews from Hungary because of otitis media. In 1947, he was adopted by his mother’s brother Alexander and his wife Helena, moved from Budapest to Nové Zámky, and his surname was changed to Lang. Alexander was interned in a camp in Nováky after being accused of trading on the black market. He attended primary and secondary school in Nové Zámky from 1948 to 1959. His school days were accompanied by displays of antisemitism not only from his peers but also from his teachers. After graduating from grammar school, he studied at a faculty in Brno and wanted to become a car designer. In his final year, he transferred to university in Prague, where he worked on machine tools, and at the same time began working at the Elektrosvit plant in Nové Zámky in the lighting wiring department. In 1966 he came up with the idea of introducing computers into the factory. Subsequently, he studied economics from 1965 to 1968, and later he completed the CSc (Candidate of Sciences degree) in Mathematics. Shortly before the Russian invasion, he left Elektrosvit and from 1 July 1968 worked in Bratislava at the Welding Research Institute. In 1969 and 1970 he worked as the head of the branch of the Research Institute of Metal Industry Prešov in Nové Zámky. When after December 1970 Nové Zámky became independent from the Prague Engineering and the Research Institute of Tools VUNAR was established, he worked at this workplace as director until September 1989, when he failed in the election for director. He is currently engaged in publishing books on the Holocaust and the history of Judaism in southern Slovakia.