I could either sign the Charter or start believing in God

Download image

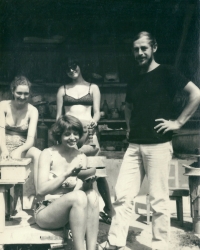

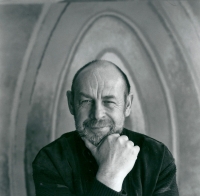

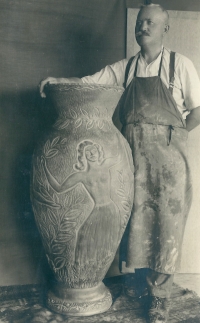

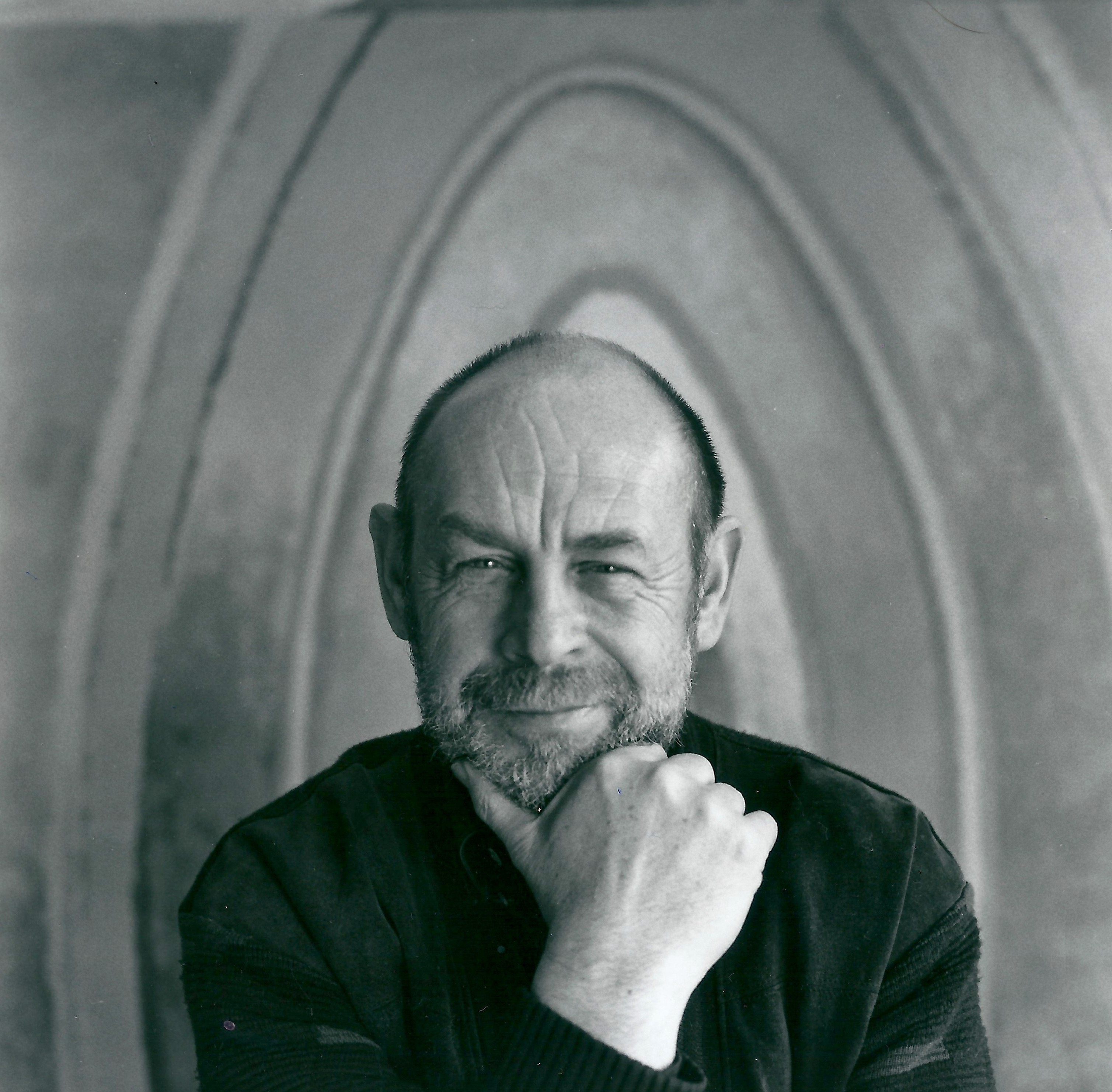

Aleš Lamr was born on 12 June 1943 in Litovel, Moravia, to a family with strong pottery-making tradition. Growing up in an inspiring environment, he had been drawing and painting himself already as an elementary school student. After 1948, his father’s workshop had been confiscated by communist authorities and the witness grew up with a stigma of being a son of a former entrepreneur. Due to this he started training as a miner but his passion for art remained undiminished. Even as a miner he found a way to develop his talent. He managed to escape a blue-collar profession by attending the Secondary school of Art and Industrial Design in Brno, studying stage design. He kept developing his unique style, that even today makes him one of the most interesting personas of the so-called grotesque painting. There was also his strong admiration for his grandfather, František Lamr, an adventurer, who had been traveling South America for several years. In the 1960s, Aleš Lamr had already moved to Prague, where he had been employed in the Military Arts Ensemble (AUS) for two years. Later, he had been working in the Barrandov film studios as an assistant director. After August 1968, he had been contemplating leaving the country. In the end, he decided to stay in Czechoslovakia. However, thanks to his sister, who married a Swedish citizen, he could travel to Western Europe. Later, he merged his life with Prague’s Lesser Part, participating in the 1981’s legendary art show ‘Courtyards of the Lesser Part’ (‘Malostranské dvorky’). He had been under State Security surveillance for quite some time. He knew Václav Havel personally. He didn’t sign the Charter 77 manifesto, yet he started believing in God. After the Velvet Revolution, he could at least pursue his artistic career freely and has been participating in art shows both home and abroad. Aleš Lamr passed away on February, the 16th, 2024.