Czechs were more receptive to us Hungarians than Slovaks were

Download image

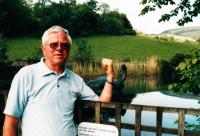

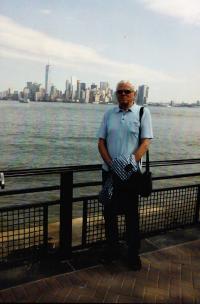

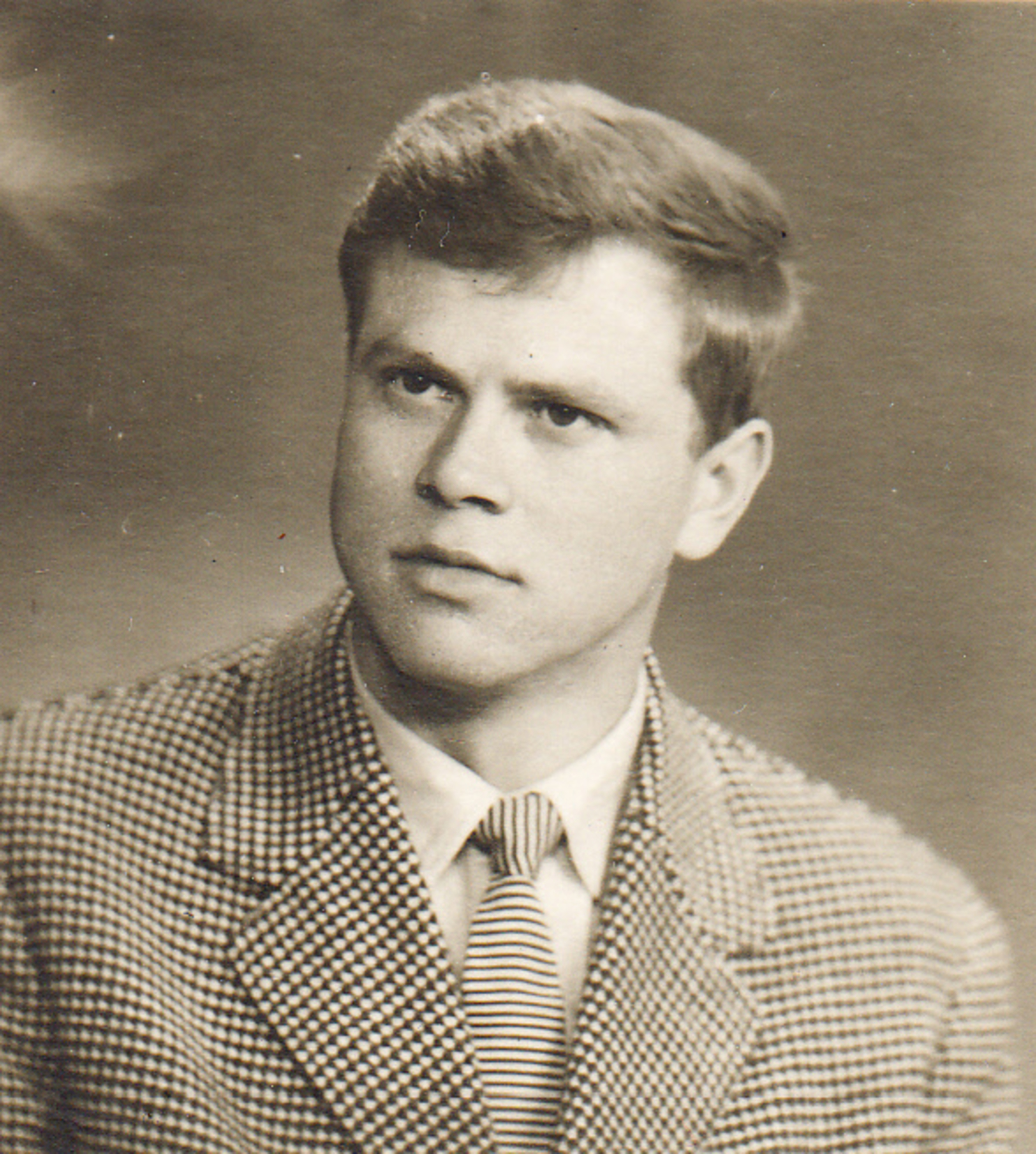

Ladislav Labancz was born on 5 August 1939 in the Hungarian village of Bátorove Kosihy, which is now part of southern Slovakia. His parents were Hungarians. He had three siblings, the family kept a farm. The village, in which the family had lived for generations, was annexed to Nazi Hungary in November 1938 as a result of the First Vienna Arbitration. His father served in the Hungarian army at the end of the war. After the war, when the territory of southern Slovakia was returned to the renewed Czechoslovakia, the Labanczes suffered anti-Hungarian repression, like all the other Hungarians in the country. The family avoided deportation presumably thanks to their relative poverty and the young age of their children. They refused to be Slovakised and continued to regard themselves as Hungarians. When the Hungarian schools were closed, Ladislav had to repeat his first year to learn Slovak. He was allowed to return to Hungarian schools after the coup in 1948, when the Communist government was pressured by the USSR to make amends for the wrongs perpetrated against the Hungarian minority and Hungarian schools were renewed. He graduated from the Hungarian secondary technical school in Košice, and during his mandatory service in the army in Bohemia, he met his future wife. They married and started a family. They lived in Teplice before moving to Prague in 1977. He feels more at ease in Bohemia than in Slovakia, where he senses a deep-rooted Hungarian-Slovak rivality. He is proud of his Hungarian ethnicity, but he considers Bohemia to be his home.