I naively believed I could help make the party and regime more humane

Download image

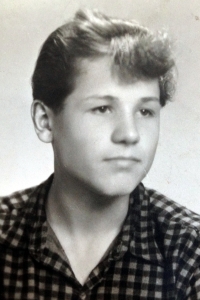

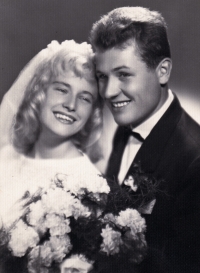

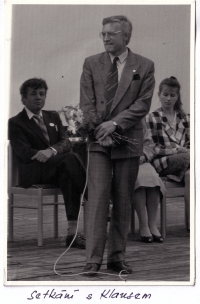

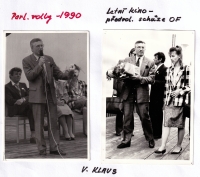

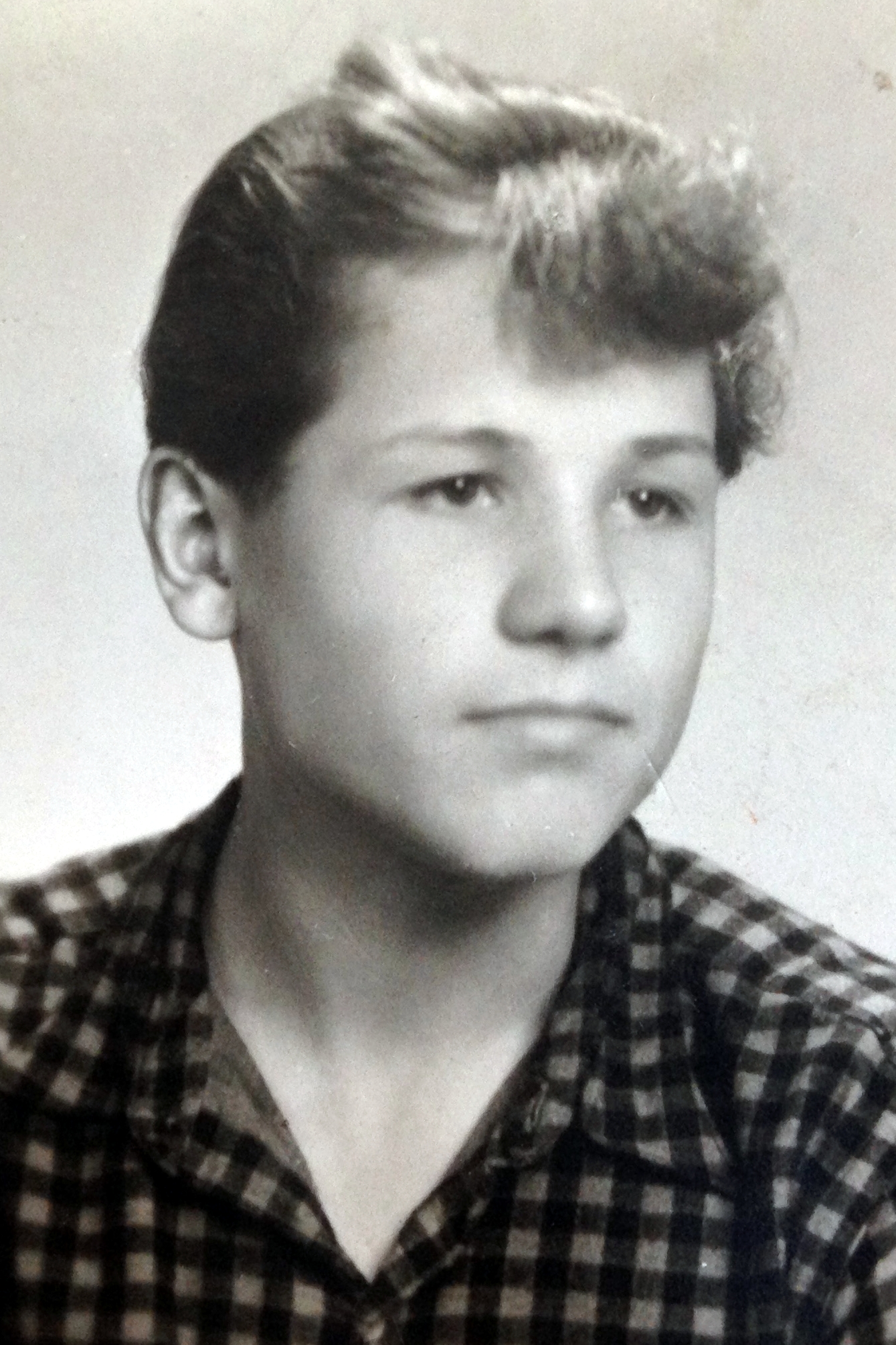

Zdeněk Kuchta was born in Hrušky near Slavkov on 4 October 1936. He witnessed the end of the war there. Romanian soldiers camped in their yard. He suffered from lower limb paralysis at age 16 and recovered. He graduated from a teaching tertiary professional school in Brno. He started working as a primary school teacher in Bílovec in northern Moravia in 1958. Then he completed part-time studies as a history and geography teacher at the university in Brno. Joined the CPC in 1967. In addition to teaching, he led the local Osvětová beseda enlightenment society and organised the cultural life in Bílovec. He supported the reform processes in 1968 and protested against the Warsaw Pact invasion after August 1968. He was expelled from the CPC and all positions. He was eventually allowed to teach, though mostly physical education, music and work education. He joined the Bílovec grammar school in the 1980s. In November 1989, he was a founding member of the Civic Forum in Bílovec. Was the Bílovec municipal chronicler for many years. Lived in Bílovec in 2022.