Only later did I realize that we were quite advanced in some respects here

Download image

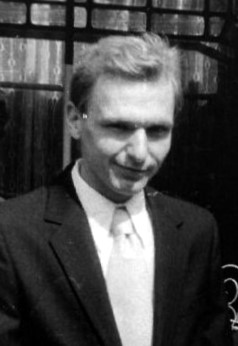

Alois Křišťan was born on August 6, 1956, in Prague into a family with deep roots in the Vysočina region, which was severely affected by communist collectivization. He spent his childhood in Prague’s Vršovice district, where he was shaped by the local Roman Catholic parish and a tourist club inspired by Scouting ideals. After graduating from high school on Přípotoční Street, he enrolled at the Faculty of Civil Engineering at the Czech Technical University. During his university studies, he joined the Salesian congregation and at the same time began studying theology illegally. Throughout the 1980s, he worked as a technician in the development and technical development department of the Armabeton company, but the focus of his life was on the spiritual community and activities of the Salesian order. In 1988, he was secretly ordained a priest, and a yearlater, he took part in a pilgrimage to Rome on the occasion of the canonization of St. Agnes of Bohemia. After the Velvet Revolution, he was appointed editor-in-chief of the newly established Christian magazine Anno Domini. In 1992, he began studying pastoral theology in Benediktbeuern, Germany. After completing his studies, he worked at the Faculty of Theology in České Budějovice, and from 2014, he taught at the Jabok College of Social Pedagogy and Theology. In 2025, he lived and worked in Prague.