Our hearts should aim for love and our minds for joy so that we do not lose what we can love

Download image

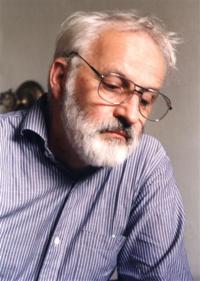

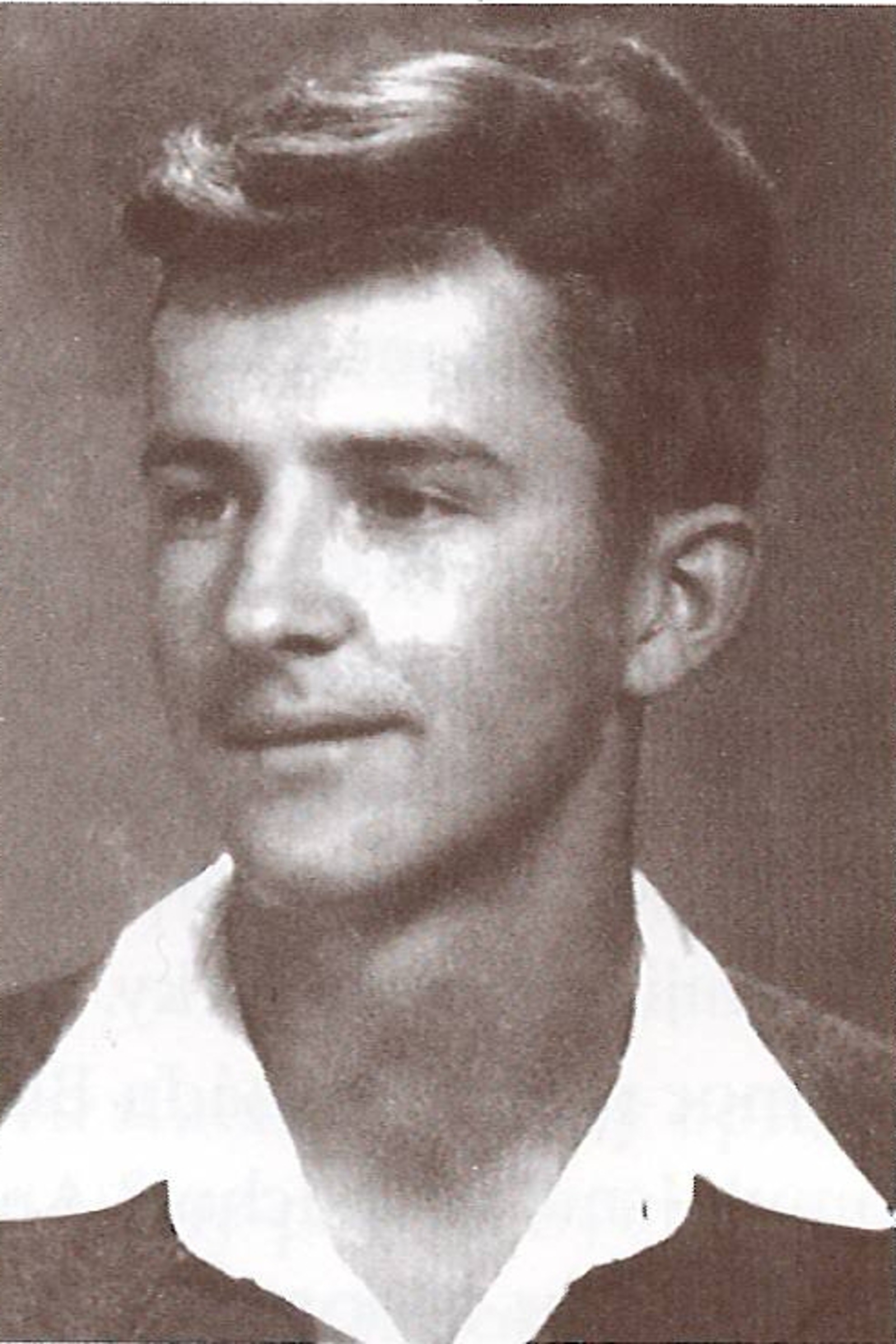

Jaroslav Krček was born April 22, 1939 in Čtyři Dvory near České Budějovice. He had a great talent for music since he was a little boy and he sang in the local church. Through self-study he learnt to play accordion when he was fourteen years old. In 1954 he was admitted to the Teaching Department of B. Jeremiáš’s Music School in České Budějovice. Then he studied at the Music Academy in Prague in the department of composition and conducting under Miloslav Kabeláč and Bohumír Liška. He completed his studies in 1967. Subsequently he moved to Pilsen to work there as a music director in the local studio of the Czechoslovak Radio. At the same time he was the conductor of the mixed choir Czech Song. After some disagreements in his workplace in Pilsen he accepted a job offer as a music director in the Supraphon company in Prague. During that time he was also active in Josef Vycpálek’s Song and Dance Ensemble. His lifelong experience and interest in folklore music inspired him to form two ensembles: Chorea Bohemia (founded in 1967, working with them until 1987) and Musica Bohemica (1975) where he is still actively involved. Chorea Bohemica focused on theatre, while Musica Bohemica is a purely musical ensemble. Jaroslav Krček is the author of many vocal, instrumental and electro-acoustic compositions.