The StB withheld his driver’s license and passport and got him fired from his job.

Download image

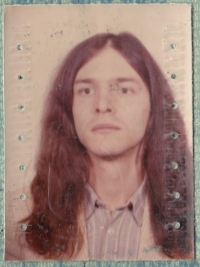

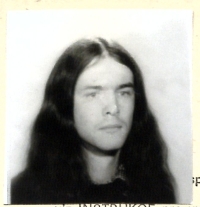

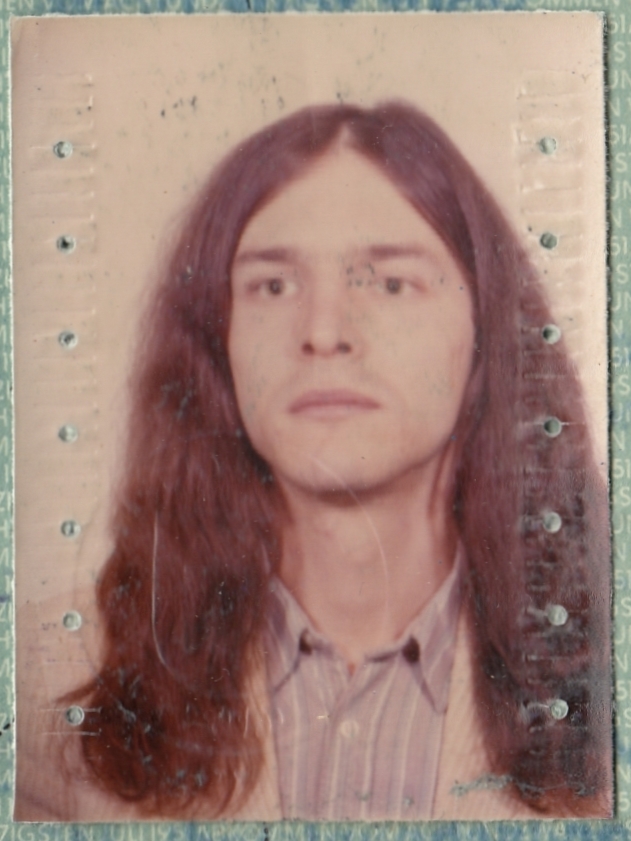

Libor Kramer, né Vraný, was born in Zlín (Gottwaldov at the time) on 13 August 1963. His parents were both chemists, and the family soon moved to Kralupy nad Vltavou, then to Pardubice. His father was expelled from the Communist Party after 1968. Ever since young age, Libor Kramer was influenced by listening to western rock music, wore long hair, and took an interest in literature. After primary school, he studied at an electrical engineering school for two years, at a secondary school of economics where he graduated. Throughout his studies he had problems with his non-conformist behaviour and appearance. He made friends with members of the Pardubice underground, attended unofficial concerts (he witnessed the brutal police crackdown on a concert in Kunětice), and read samizdat. Later, as a Mototechna employee, he published and distributed a literary samizdat magazine and leaflets condemning the deployment of Soviet SS-20 missiles in Czechoslovakia with friends. As a result, the State Security became interested in him. Interrogations, searches, threats of several years of punishment, and offers to cooperate with the secret police followed. At the same time, Kramer was about to serve in the military. In 1984, he attempted suicide, which resulted in a three-month psychiatric hospitalization. Thanks to a favorable medical report, the army wrote him off as unfit for military service and he even avoided trial over of his activities with a samizdat magazine and leaflets. At least the StB withheld his driving licence and passport and got him fired from railroad mail service. This is when Libor Kramer decided to emigrate. He got his passport back, went on a skiing trip to Yugoslavia on 28 February 1987, and then crossed over to Austria. He wanted to go on to the United States, but the situation in the Austrian refugee camp in Traiskirchen soon forced him to leave illegally for West Germany. With his knowledge of German, he quickly gained a foothold in Munich and was granted political asylum. He freelanced for an advertising agency and earned extra money by delivering bread in the mornings. In Munich, he also met famous Czech émigrés such as Milan Kubes, Karel Kryl and Svatopluk Karásek. He took part in several meetings with Czechoslovak youth in Budapest, organized by Radio Free Europe in the late 1980s, where he brought exile literature. He got married in Germany and adopted his wife’s name. From the late 1990s, Libor Kramer worked for a translation agency focusing on former communist countries. He returned to the Czech Republic in 2000. He received an award as a participant in the anti-communist resistance.