You can win even in a situation that has a no way out. But you need to sacrifice a lot

Download image

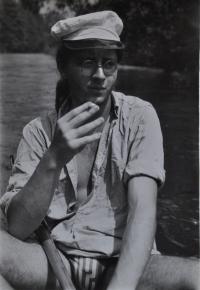

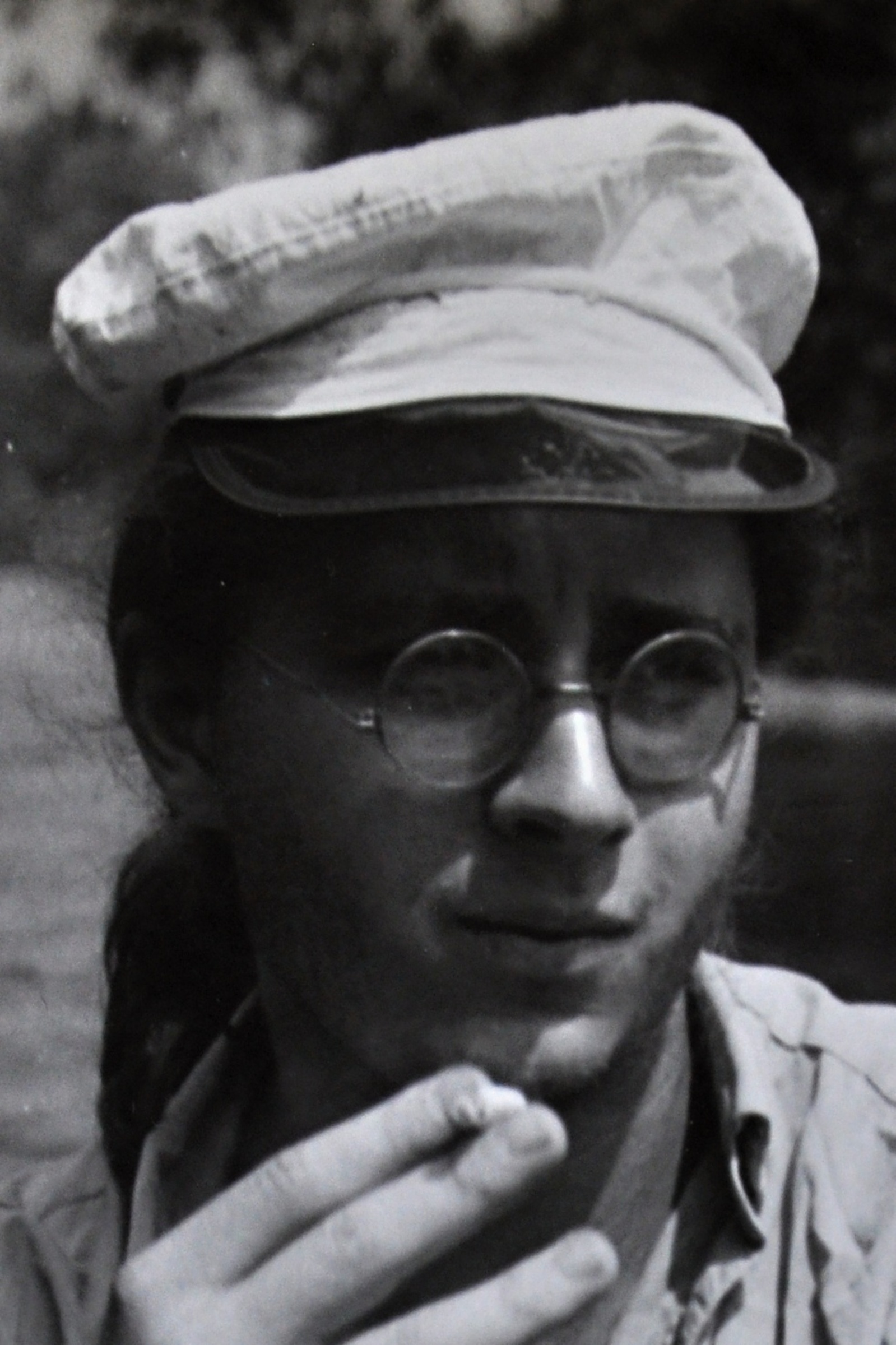

Jan Král was born on December 21, 1967 in Ostrava in a family of a civil engineer and a doctor. After graduation from grammar school he began working in the Zdeněk Nejedlý Theatre as a stagehand. Jan was regularly going from Ostrava to see festivals and concerts associated with the underground movement and he was thus gradually getting to know people from the dissent. In order to avoid military service in the Czechoslovak People’s Army, he pretended a suicide attempt. After a stay in a psychiatric hospital he was eventually released from the obligation of military service. Jan was involved in writing, copying and distribution of samizdat literature. He was under the surveillance of the State Security Police and he was regularly being interrogated. In January 1989 he signed the declaration of Charter 77. He was subsequently detained while having a petition for release of Václav Havel from prison in his possession and he faced criminal prosecution. After November 1989 he worked as a journalist in the daily newspapers Moravskoslezský den, Český deník and Lidové Noviny.