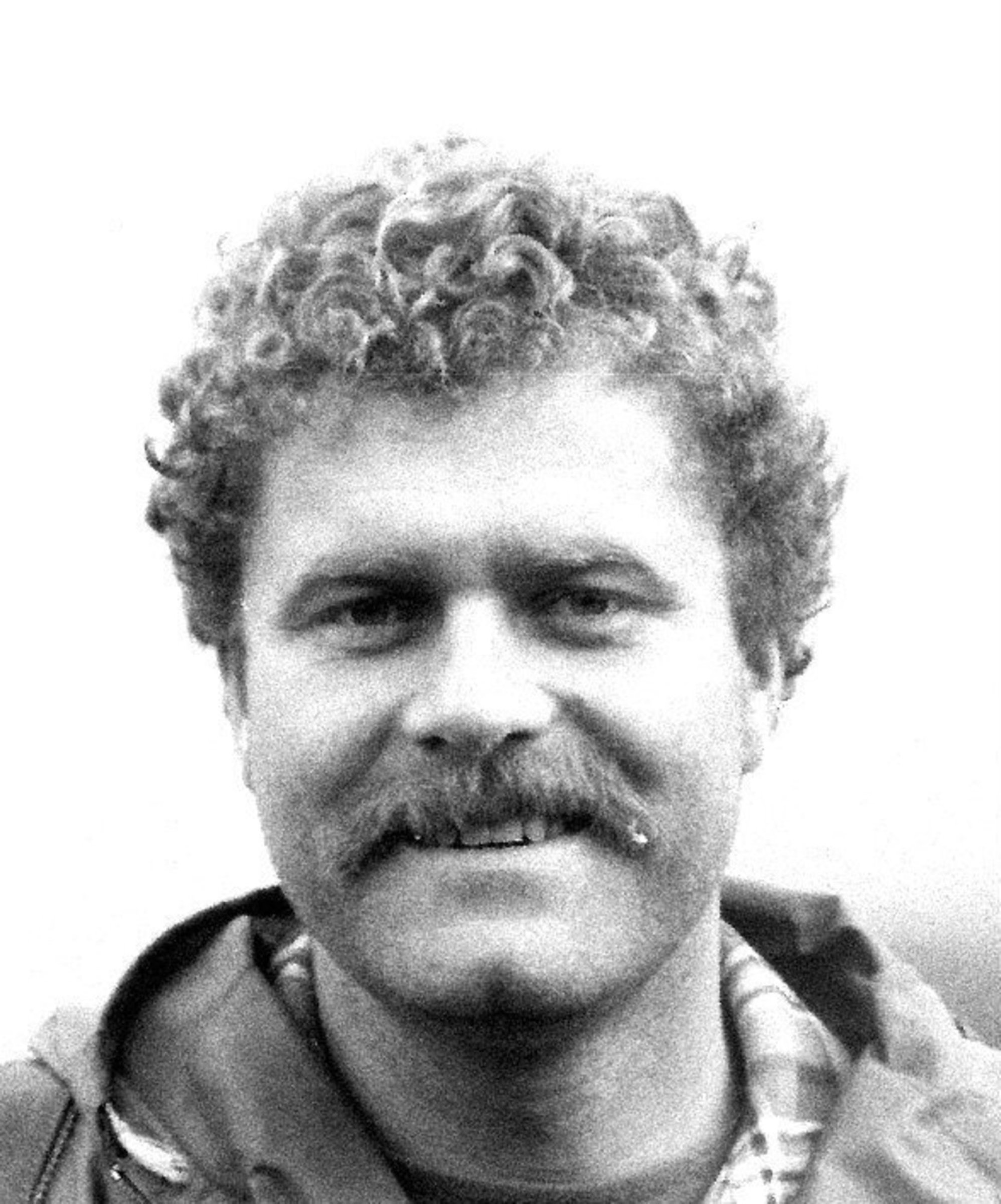

Defending freedom always comes with a cost

Download image

Jan Kozák was born on 21 May 1951 in Prague. His father worked as an economist at E. F. Burian Theatre and later as the chief economist of Prague theatres. In 1968 he gave public support to the Prague Spring movement and was subsequently expelled from the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (CPC). For the young student, humane socialism remained a source of great inspiration. His idealistic stance hindered his studies of history and archiving at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. Jan Kozák refused to join the Socialist Youth Union (SYU), and together with his friend Oldřich Tůma he made a stand against the discrimination of non-unionised students. The faculty expelled them both, and Jan Kozák received a suspended sentence of nine months in prison for allegedly assaulting his colleague Gombár. He underwent mandatory military service in a tank regiment under the secret surveillance of the Military Counter-Intelligence. The secret agent collected enough material to bring Private Kozák to trial. The court returned a sentence of nine month in prison, this time for real. Kozák served part of his term in Pankrác, but the second part in the labour camp in Dříň near Kladno proved to be a much rougher ordeal. He was exhausted by work at the local rolling mill and had to be hospitalised. After he was released from hospital, he was set to lighter employment until he completed his sentence in 1977. However, he did not change his political views. He learnt Sanskrit and established a publishing house called Biblioteca Gnostica, which he continues to manage to this day.