You had let the Germans fool you, and now you would be toiling here as an idiot?

Download image

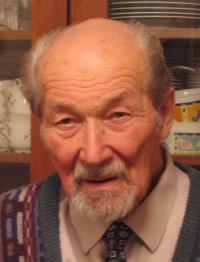

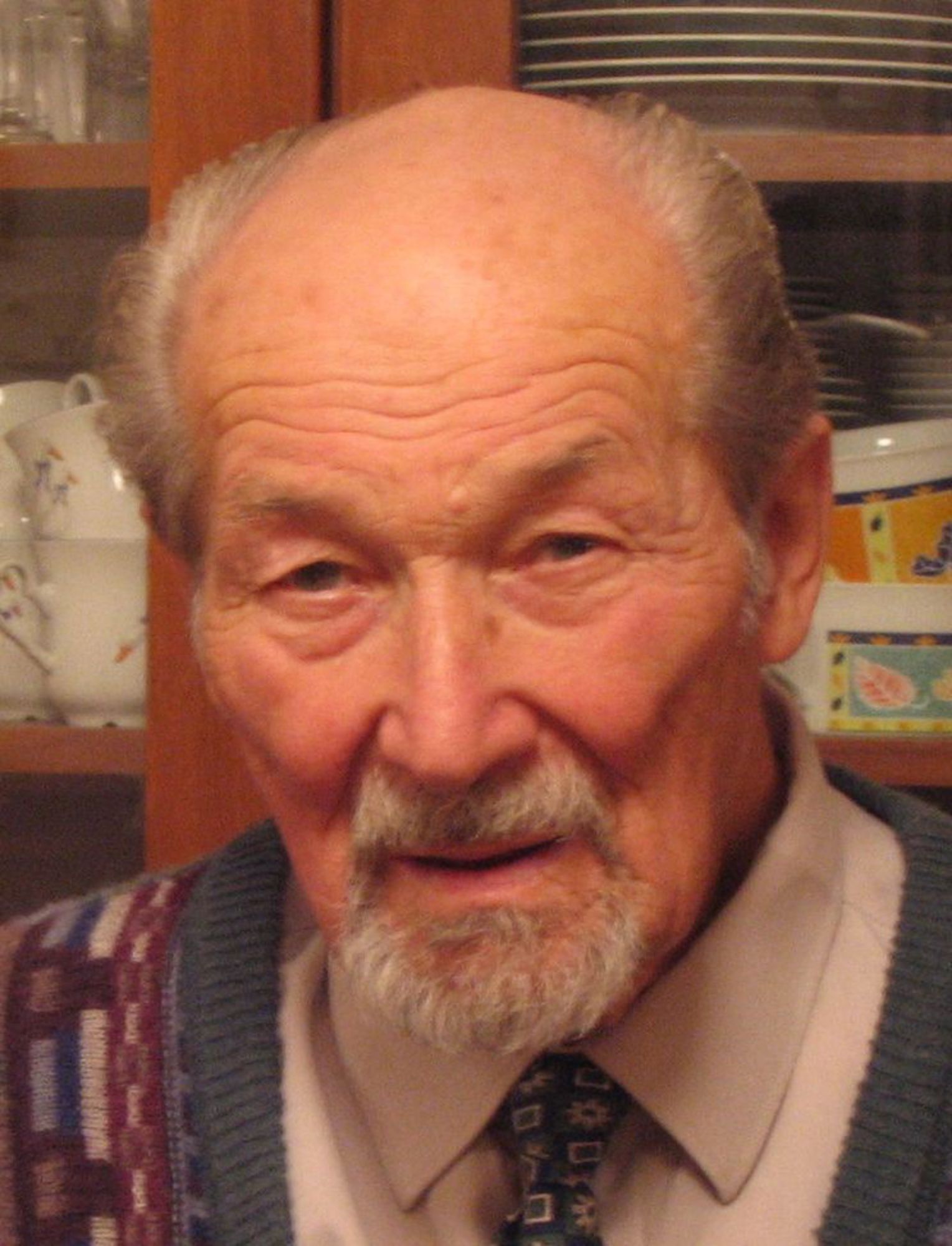

Ludvík Korcz was born July 26, 1920 in Třanovice in the Těšín region. In 1939 he joined the Czechoslovak army, but he was dismissed from it after the establishment of the Protectorate. He moved in with his friends who lived close to the new Polish border and he guided several refugees, especially Jews, over the borderline. He was arrested by the Gestapo for taking people over the border, and subsequently he was sent to do forced labour in Germany in 1939-1940. He registered as a person of Silesian nationality, without realizing the full import thereof - in 1940 he was drafted to the Wehrmacht - to a signal unit. He experienced the campaign in the Balkans (Greece), in 1941 he was deployed on the eastern front and taken captive near the town of Pillau (Baltiysk), and until September, 1945 he was held in a prisoner-of-war camp in Siberia (where he held an advantageous position as an interpreter). In 1946 he began his service in the Czechoslovak army and then he worked for the State Administration, in the transport industry (car repairs).