I myself wasn’t bullied by the communists, but I thought of my father, who died prematurely because of them

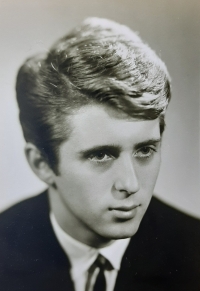

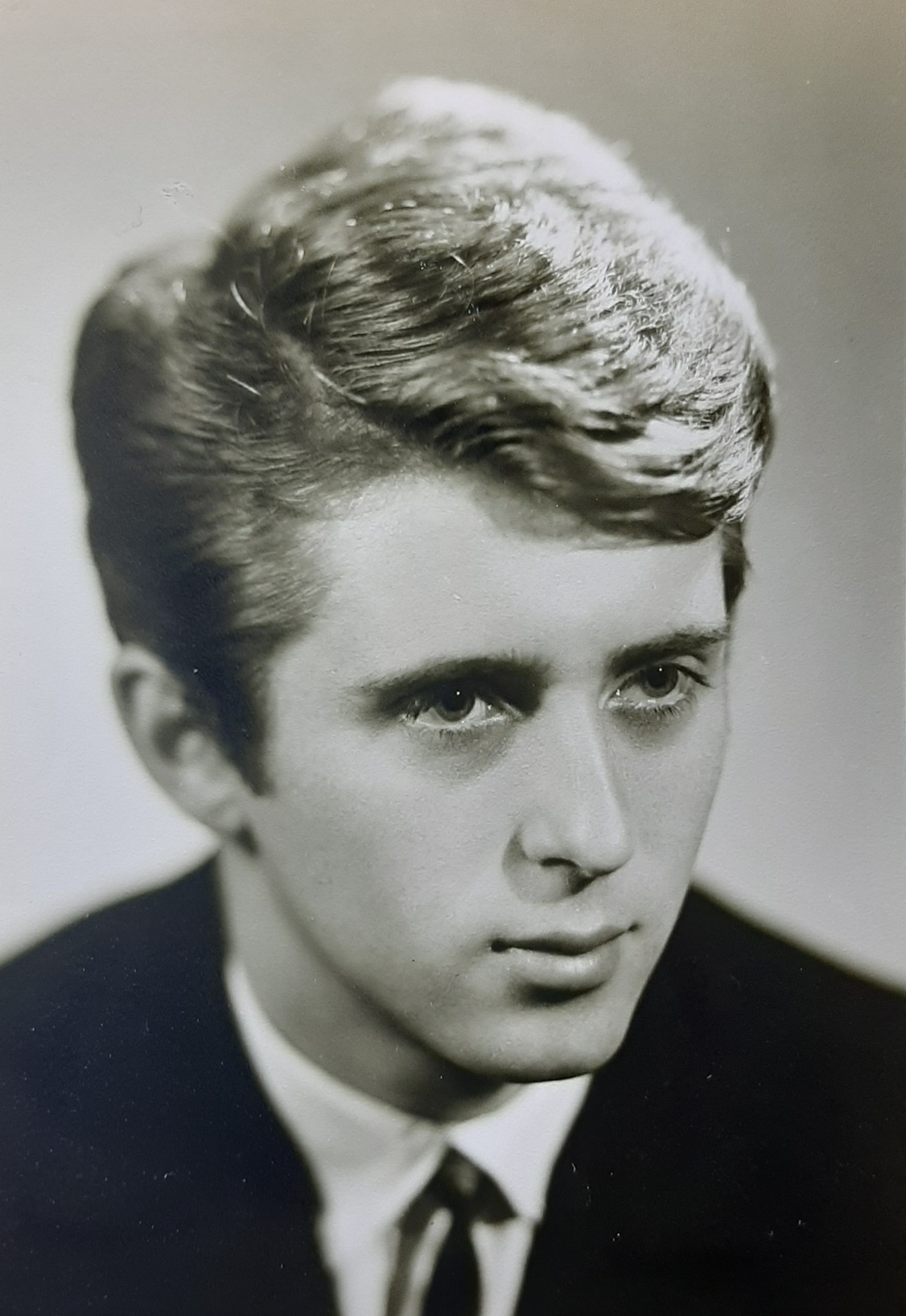

Download image

Ludvík Kolský was born on 24 February 1947 in Příbram as the youngest of three children. His mother had a ladies’ hat shop in Pražská Street, and his father worked as a bank clerk. In the 1950s, his father refused to cooperate with State Security and confided this to his colleagues at work. Someone turned him in, and he spent more than three years in the uranium camps in the Jáchymov region. He died prematurely in the early 1960s. Ludvík Kolský graduated from the secondary industrial school in Příbram, majoring in mineral processing, then worked at the Příbram Ore and Uranium Mines, first as a dosimetrist, later as chief geophysicist. He attended the Příbram Sokol, which continued to operate under the heading of a physical education union, and his sons attended the illegal Brdy pack scout troop, which was run as a hiking troop. Between 1966 and 1968, he served his basic military service in Prostějov with the paratroopers. He studied at the medical school there for half a year and spent the rest of his service as a medic. Here he also experienced the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact troops in August 1968, when Soviet soldiers occupied the barracks and confiscated the soldiers’ weapons. After Jan Palach burned to death in January 1969, he and his friends attended his funeral in Prague, leading the procession with the Czechoslovak flag. When the communist regime began to collapse in the autumn of 1989, he took part in protests and meetings in the cultural centre in Příbram. After the uranium mining in Příbram ended in 1991, he moved to the SÚJCHBO (State Institute of Nuclear, Chemical and Biological Protection) in Kamenná near Příbram, where he worked as a radon measurer until his retirement. In 1992, he participated in the founding of the Prokop Mining Association. Today, he is a guide at the Anna Mine in the Mining Museum in Příbram. In 2025, he lived in Příbram.