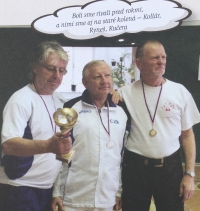

Gabriel received a penalty for good representation in a fencing tournament

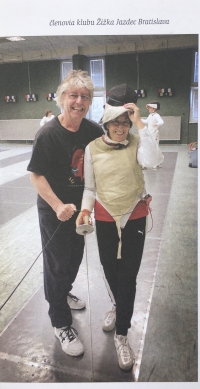

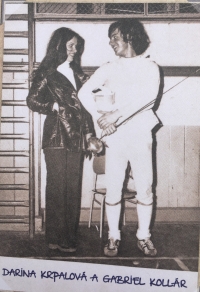

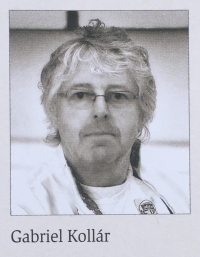

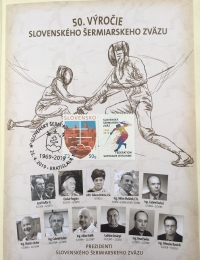

Gabriel Kollár was born in 1952 in Bratislava, into a family of hungarian nationality. His father was a sports journalist. In 1969 he founded the Slovak Fencing Association. He was fifteen years old when the Warsaw Pact invasion broke out. In 1971 he became the junior champion of Czechoslovakia. He is still actively involved in fencing. He graduated from the University of Economics in Bratislava. During the military service, he was in Dukla Olomouc, for which he fenced. He did first class coaching at Karlova University. After ten years, he left the Czechoslovak national team and started working as a sports editor at Slovak television. In 1980, he completed postgraduate studies in journalism at Comenius University in Bratislava. A year before the outbreak of the Gentle Revolution, he left for Kuwait. He worked there as a fencing coach. When he was on holiday in Slovakia in 1989, demonstrations began. He filmed them on a private camera. From 1994 to 1996 he was the president of the Slovak Fencing Association. After the revolution, he worked for a German software company. After that, he worked for seven years as a marketing director at “The first building bank”. For a year, he accepted an offer to be a member of the board of directors of the newly formed Allianz Slovakia. In 2000, he joined the First Supplementary Pension Insurance Company. In 2008, he accepted an offer to launch the sports channel of public television STV3. He regularly participates in veteran tournaments abroad. He has been training slovak fencers for more than three decades.