To have no enemies in your life

Download image

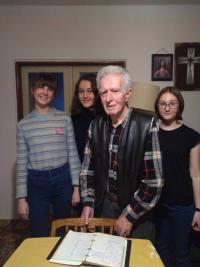

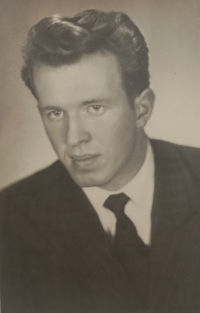

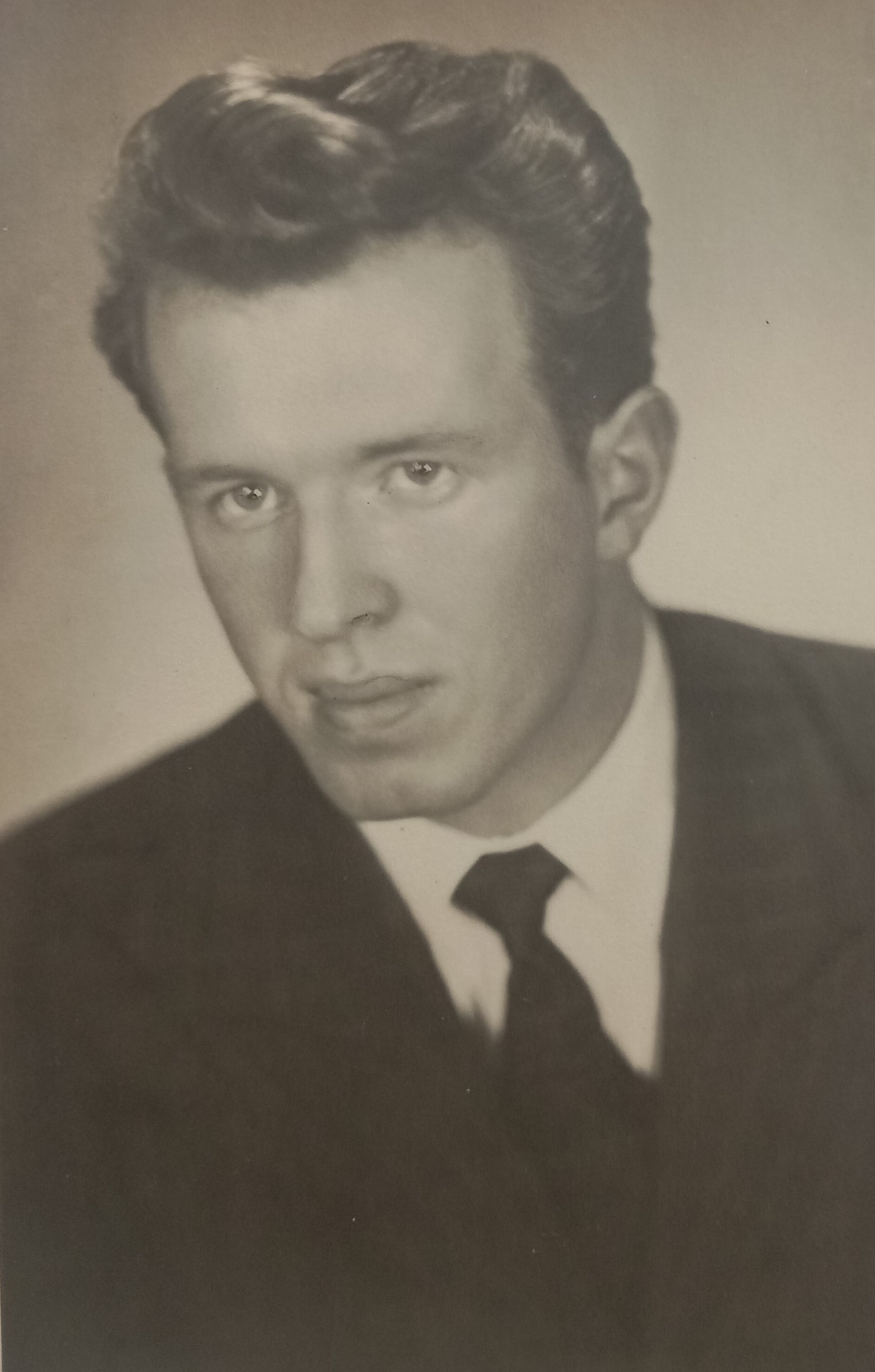

Vladimír Kolář was born on 17 January 1936 in Temelínec as the second of three sons of a farmer. As a small boy, he had to help out on the farm, he tied sheaves into stacks, ploughed, and gathered hay. He was brought up to be devout in his beliefs and respectful in his work. His earliest memory is of his father departing on a train to protect the borders during the general mobilisation on 2 October 1938 and how he returned home two days later because the Munich Agreement was signed. His mother’s brother was a member of the Financial Guard in Přední Výtoň before the war and later helped the partisans as a messenger. The witness started elementary school in Křtěnov in 1942; the school was later moved to Temelín by the Germans. After completing four years of town school (upper primary) in Týn nad Vltavou, Vladimír Kolář was barred from continuing his studies because of his origin - his family owned 18 hectares of fields and forests. On the intercession of a family friend, he was allowed to train as a toolmaker at Kovosvit in Sezimovo Ústí. He was assigned to a job at the arms works in Strakonice, where he attended a two-year evening course at a secondary technical school. His aunt, a doctor, arranged for him to be allowed to study at a technical school in Písek. After two years of military service in Olomouc, he was employed at Kovosvit in Sezimovo Ústí; he married and had three children. His father-in-law was a member of the resistance group Šumava II during the war. After four years at Kovosvit, Vladimír Kolář worked himself into the construction department, where he remained until his retirement in 1996. In August 1968 he and his wife considered emigrating to Austria, but in the end they decided to stay in Czechoslovakia due to their old parents. In 1988 the state confiscated their house and lands to make way for the Temelín nuclear power plant. After 1989 he was disgusted how the Communists just turned coat and now pretend to be democrats.