I’m not going to tell anyone to believe in God - seek, and seek earnestly

Download image

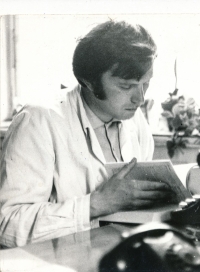

Jan Kofroň was born on June 8, 1944 in Prague. His father was a lawyer and a judge and was dismissed from the Ministry of Justice immediately after the February 1948 coup. The dismissal influenced Jan’s later life. He had wished to study geology, but because of the bad cadre assessment he was only allowed to study agriculture school. After the military service, he worked at agriculture companies Agroprojekt and Oseva. In 1968, he took the opportunity to travel to Italy with his friends, where he also heard about the August occupation. Since his youth he wanted to become a priest, but later he changed his mind and got married in 1972. He and his wife then secretly used to meet other religious young couples. In 1988, Jan took the opportunity to be ordained a priest in the underground church even though we was a married man. After the Velvet Revolution, he worked at Charles University, the Ministry of Education, and collaborated with Bishop Václav Malý. At the time of the interview he was working in a hospice and a psychiatric hospital.